illegitimate

Rollingstone.com

The Worst President in History?

One of America's leading historians assesses George W. Bush

Posted Apr 21, 2006 12:34 PM

Flashback: Bush in '99 -- We Warned You!

George W. Bush's presidency appears headed for colossal historical disgrace. Barring a cataclysmic event on the order of the terrorist attacks of September 11th, after which the public might rally around the White House once again, there seems to be little the administration can do to avoid being ranked on the lowest tier of U.S. presidents. And that may be the best-case scenario. Many historians are now wondering whether Bush, in fact, will be remembered as the very worst president in all of American history.

From time to time, after hours, I kick back with my colleagues at Princeton to argue idly about which president really was the worst of them all. For years, these perennial debates have largely focused on the same handful of chief executives whom national polls of historians, from across the ideological and political spectrum, routinely cite as the bottom of the presidential barrel. Was the lousiest James Buchanan, who, confronted with Southern secession in 1860, dithered to a degree that, as his most recent biographer has said, probably amounted to disloyalty -- and who handed to his successor, Abraham Lincoln, a nation already torn asunder? Was it Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson, who actively sided with former Confederates and undermined Reconstruction? What about the amiably incompetent Warren G. Harding, whose administration was fabulously corrupt? Or, though he has his defenders, Herbert Hoover, who tried some reforms but remained imprisoned in his own outmoded individualist ethic and collapsed under the weight of the stock-market crash of 1929 and the Depression's onset? The younger historians always put in a word for Richard M. Nixon, the only American president forced to resign from office.

Now, though, George W. Bush is in serious contention for the title of worst ever. In early 2004, an informal survey of 415 historians conducted by the nonpartisan History News Network found that eighty-one percent considered the Bush administration a "failure." Among those who called Bush a success, many gave the president high marks only for his ability to mobilize public support and get Congress to go along with what one historian called the administration's "pursuit of disastrous policies." In fact, roughly one in ten of those who called Bush a success was being facetious, rating him only as the best president since Bill Clinton -- a category in which Bush is the only contestant.

The lopsided decision of historians should give everyone pause. Contrary to popular stereotypes, historians are generally a cautious bunch. We assess the past from widely divergent points of view and are deeply concerned about being viewed as fair and accurate by our colleagues. When we make historical judgments, we are acting not as voters or even pundits, but as scholars who must evaluate all the evidence, good, bad or indifferent. Separate surveys, conducted by those perceived as conservatives as well as liberals, show remarkable unanimity about who the best and worst presidents have been.

Historians do tend, as a group, to be far more liberal than the citizenry as a whole -- a fact the president's admirers have seized on to dismiss the poll results as transparently biased. One pro-Bush historian said the survey revealed more about "the current crop of history professors" than about Bush or about Bush's eventual standing. But if historians were simply motivated by a strong collective liberal bias, they might be expected to call Bush the worst president since his father, or Ronald Reagan, or Nixon. Instead, more than half of those polled -- and nearly three-fourths of those who gave Bush a negative rating -- reached back before Nixon to find a president they considered as miserable as Bush. The presidents most commonly linked with Bush included Hoover, Andrew Johnson and Buchanan. Twelve percent of the historians polled -- nearly as many as those who rated Bush a success -- flatly called Bush the worst president in American history. And these figures were gathered before the debacles over Hurricane Katrina, Bush's role in the Valerie Plame leak affair and the deterioration of the situation in Iraq. Were the historians polled today, that figure would certainly be higher.

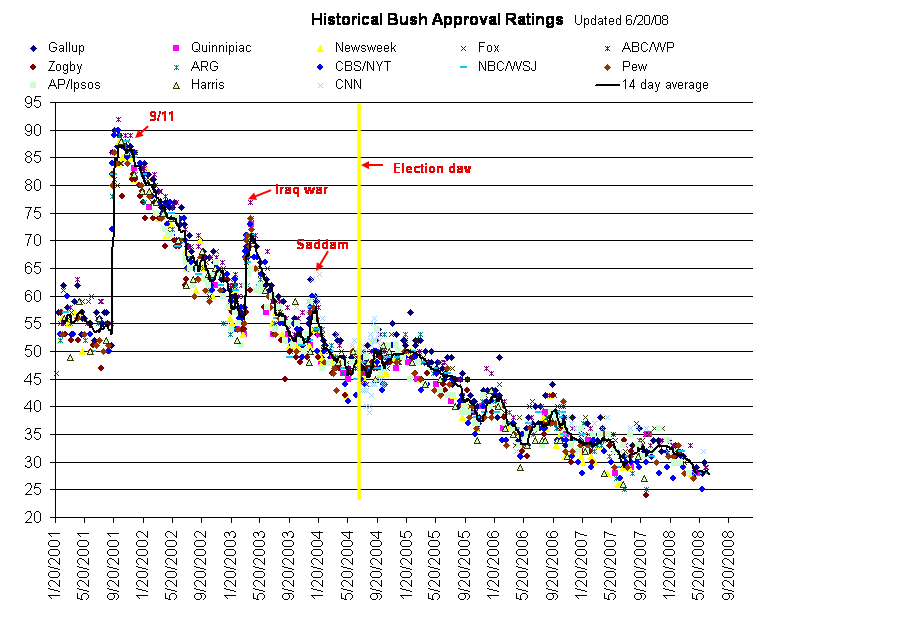

Even worse for the president, the general public, having once given Bush the highest approval ratings ever recorded, now appears to be coming around to the dismal view held by most historians. To be sure, the president retains a considerable base of supporters who believe in and adore him, and who reject all criticism with a mixture of disbelief and fierce contempt -- about one-third of the electorate. (When the columnist Richard Reeves publicized the historians' poll last year and suggested it might have merit, he drew thousands of abusive replies that called him an idiot and that praised Bush as, in one writer's words, "a Christian who actually acts on his deeply held beliefs.") Yet the ranks of the true believers have thinned dramatically. A majority of voters in forty-three states now disapprove of Bush's handling of his job. Since the commencement of reliable polling in the 1940s, only one twice-elected president has seen his ratings fall as low as Bush's in his second term: Richard Nixon, during the months preceding his resignation in 1974. No two-term president since polling began has fallen from such a height of popularity as Bush's (in the neighborhood of ninety percent, during the patriotic upswell following the 2001 attacks) to such a low (now in the midthirties). No president, including Harry Truman (whose ratings sometimes dipped below Nixonian levels), has experienced such a virtually unrelieved decline as Bush has since his high point. Apart from sharp but temporary upticks that followed the commencement of the Iraq war and the capture of Saddam Hussein, and a recovery during the weeks just before and after his re-election, the Bush trend has been a profile in fairly steady disillusionment.

* * * *

How does any president's reputation sink so low? The reasons are best understood as the reverse of those that produce presidential greatness. In almost every survey of historians dating back to the 1940s, three presidents have emerged as supreme successes: George Washington, Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt. These were the men who guided the nation through what historians consider its greatest crises: the founding era after the ratification of the Constitution, the Civil War, and the Great Depression and Second World War. Presented with arduous, at times seemingly impossible circumstances, they rallied the nation, governed brilliantly and left the republic more secure than when they entered office.

Calamitous presidents, faced with enormous difficulties -- Buchanan, Andrew Johnson, Hoover and now Bush -- have divided the nation, governed erratically and left the nation worse off. In each case, different factors contributed to the failure: disastrous domestic policies, foreign-policy blunders and military setbacks, executive misconduct, crises of credibility and public trust. Bush, however, is one of the rarities in presidential history: He has not only stumbled badly in every one of these key areas, he has also displayed a weakness common among the greatest presidential failures -- an unswerving adherence to a simplistic ideology that abjures deviation from dogma as heresy, thus preventing any pragmatic adjustment to changing realities. Repeatedly, Bush has undone himself, a failing revealed in each major area of presidential performance.

* * * *

THE CREDIBILITY GAP

No previous president appears to have squandered the public's trust more than Bush has. In the 1840s, President James Polk gained a reputation for deviousness over his alleged manufacturing of the war with Mexico and his supposedly covert pro-slavery views. Abraham Lincoln, then an Illinois congressman, virtually labeled Polk a liar when he called him, from the floor of the House, "a bewildered, confounded and miserably perplexed man" and denounced the war as "from beginning to end, the sheerest deception." But the swift American victory in the war, Polk's decision to stick by his pledge to serve only one term and his sudden death shortly after leaving office spared him the ignominy over slavery that befell his successors in the 1850s. With more than two years to go in Bush's second term and no swift victory in sight, Bush's reputation will probably have no such reprieve.

The problems besetting Bush are of a more modern kind than Polk's, suited to the television age -- a crisis both in confidence and credibility. In 1965, Lyndon Johnson's Vietnam travails gave birth to the phrase "credibility gap," meaning the distance between a president's professions and the public's perceptions of reality. It took more than two years for Johnson's disapproval rating in the Gallup Poll to reach fifty-two percent in March 1968 -- a figure Bush long ago surpassed, but that was sufficient to persuade the proud LBJ not to seek re-election. Yet recently, just short of three years after Bush buoyantly declared "mission accomplished" in Iraq, his disapproval ratings have been running considerably higher than Johnson's, at about sixty percent. More than half the country now considers Bush dishonest and untrustworthy, and a decisive plurality consider him less trustworthy than his predecessor, Bill Clinton -- a figure still attacked by conservative zealots as "Slick Willie."

Previous modern presidents, including Truman, Reagan and Clinton, managed to reverse plummeting ratings and regain the public's trust by shifting attention away from political and policy setbacks, and by overhauling the White House's inner circles. But Bush's publicly expressed view that he has made no major mistakes, coupled with what even the conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr. calls his "high-flown pronouncements" about failed policies, seems to foreclose the first option. Upping the ante in the Middle East and bombing Iranian nuclear sites, a strategy reportedly favored by some in the White House, could distract the public and gain Bush immediate political capital in advance of the 2006 midterm elections -- but in the long term might severely worsen the already dire situation in Iraq, especially among Shiite Muslims linked to the Iranians. And given Bush's ardent attachment to loyal aides, no matter how discredited, a major personnel shake-up is improbable, short of indictments. Replacing Andrew Card with Joshua Bolten as chief of staff -- a move announced by the president in March in a tone that sounded more like defiance than contrition -- represents a rededication to current policies and personnel, not a serious change. (Card, an old Bush family retainer, was widely considered more moderate than most of the men around the president and had little involvement in policy-making.) The power of Vice President Dick Cheney, meanwhile, remains uncurbed. Were Cheney to announce he is stepping down due to health problems, normally a polite pretext for a political removal, one can be reasonably certain it would be because Cheney actually did have grave health problems.

* * * *

BUSH AT WAR

Until the twentieth century, American presidents managed foreign wars well -- including those presidents who prosecuted unpopular wars. James Madison had no support from Federalist New England at the outset of the War of 1812, and the discontent grew amid mounting military setbacks in 1813. But Federalist political overreaching, combined with a reversal of America's military fortunes and the negotiation of a peace with Britain, made Madison something of a hero again and ushered in a brief so-called Era of Good Feelings in which his Jeffersonian Republican Party coalition ruled virtually unopposed. The Mexican War under Polk was even more unpopular, but its quick and victorious conclusion redounded to Polk's favor -- much as the rapid American victory in the Spanish-American War helped William McKinley overcome anti-imperialist dissent.

The twentieth century was crueler to wartime presidents. After winning re-election in 1916 with the slogan "He Kept Us Out of War," Woodrow Wilson oversaw American entry into the First World War. Yet while the doughboys returned home triumphant, Wilson's idealistic and politically disastrous campaign for American entry into the League of Nations presaged a resurgence of the opposition Republican Party along with a redoubling of American isolationism that lasted until Pearl Harbor.Bush has more in common with post-1945 Democratic presidents Truman and Johnson, who both became bogged down in overseas military conflicts with no end, let alone victory, in sight. But Bush has become bogged down in a singularly crippling way. On September 10th, 2001, he held among the lowest ratings of any modern president for that point in a first term. (Only Gerald Ford, his popularity reeling after his pardon of Nixon, had comparable numbers.) The attacks the following day transformed Bush's presidency, giving him an extraordinary opportunity to achieve greatness. Some of the early signs were encouraging. Bush's simple, unflinching eloquence and his quick toppling of the Taliban government in Afghanistan rallied the nation. Yet even then, Bush wasted his chance by quickly choosing partisanship over leadership.

No other president -- Lincoln in the Civil War, FDR in World War II, John F. Kennedy at critical moments of the Cold War -- faced with such a monumental set of military and political circumstances failed to embrace the opposing political party to help wage a truly national struggle. But Bush shut out and even demonized the Democrats. Top military advisers and even members of the president's own Cabinet who expressed any reservations or criticisms of his policies -- including retired Marine Corps Gen. Anthony Zinni and former Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill -- suffered either dismissal, smear attacks from the president's supporters or investigations into their alleged breaches of national security. The wise men who counseled Bush's father, including James Baker and Brent Scowcroft, found their entreaties brusquely ignored by his son. When asked if he ever sought advice from the elder Bush, the president responded, "There is a higher Father that I appeal to."

All the while, Bush and the most powerful figures in the administration, Vice President Dick Cheney and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, were planting the seeds for the crises to come by diverting the struggle against Al Qaeda toward an all-out effort to topple their pre-existing target, Saddam Hussein. In a deliberate political decision, the administration stampeded the Congress and a traumatized citizenry into the Iraq invasion on the basis of what has now been demonstrated to be tendentious and perhaps fabricated evidence of an imminent Iraqi threat to American security, one that the White House suggested included nuclear weapons. Instead of emphasizing any political, diplomatic or humanitarian aspects of a war on Iraq -- an appeal that would have sounded too "sensitive," as Cheney once sneered -- the administration built a "Bush Doctrine" of unprovoked, preventive warfare, based on speculative threats and embracing principles previously abjured by every previous generation of U.S. foreign policy-makers, even at the height of the Cold War. The president did so with premises founded, in the case of Iraq, on wishful thinking. He did so while proclaiming an expansive Wilsonian rhetoric of making the world safe for democracy -- yet discarding the multilateralism and systems of international law (including the Geneva Conventions) that emanated from Wilson's idealism. He did so while dismissing intelligence that an American invasion could spark a long and bloody civil war among Iraq's fierce religious and ethnic rivals, reports that have since proved true. And he did so after repeated warnings by military officials such as Gen. Eric Shinseki that pacifying postwar Iraq would require hundreds of thousands of American troops -- accurate estimates that Paul Wolfowitz and other Bush policy gurus ridiculed as "wildly off the mark."

When William F. Buckley, the man whom many credit as the founder of the modern conservative movement, writes categorically, as he did in February, that "one can't doubt that the American objective in Iraq has failed," then something terrible has happened. Even as a brash young iconoclast, Buckley always took the long view. The Bush White House seems incapable of doing so, except insofar as a tiny trusted circle around the president constantly reassures him that he is a messianic liberator and profound freedom fighter, on a par with FDR and Lincoln, and that history will vindicate his every act and utterance.

* * * *

BUSH AT HOME

Bush came to office in 2001 pledging to govern as a "compassionate conservative," more moderate on domestic policy than the dominant right wing of his party. The pledge proved hollow, as Bush tacked immediately to the hard right. Previous presidents and their parties have suffered when their actions have belied their campaign promises. Lyndon Johnson is the most conspicuous recent example, having declared in his 1964 run against the hawkish Republican Barry Goldwater that "we are not about to send American boys nine or ten thousand miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves." But no president has surpassed Bush in departing so thoroughly from his original campaign persona.

The heart of Bush's domestic policy has turned out to be nothing more than a series of massively regressive tax cuts -- a return, with a vengeance, to the discredited Reagan-era supply-side faith that Bush's father once ridiculed as "voodoo economics." Bush crowed in triumph in February 2004, "We cut taxes, which basically meant people had more money in their pocket." The claim is bogus for the majority of Americans, as are claims that tax cuts have led to impressive new private investment and job growth. While wiping out the solid Clinton-era federal surplus and raising federal deficits to staggering record levels, Bush's tax policies have necessitated hikes in federal fees, state and local taxes, and co-payment charges to needy veterans and families who rely on Medicaid, along with cuts in loan programs to small businesses and college students, and in a wide range of state services. The lion's share of benefits from the tax cuts has gone to the very richest Americans, while new business investment has increased at a historically sluggish rate since the peak of the last business cycle five years ago. Private-sector job growth since 2001 has been anemic compared to the Bush administration's original forecasts and is chiefly attributable not to the tax cuts but to increased federal spending, especially on defense. Real wages for middle-income Americans have been dropping since the end of 2003: Last year, on average, nominal wages grew by only 2.4 percent, a meager gain that was completely erased by an average inflation rate of 3.4 percent.

The monster deficits, caused by increased federal spending combined with the reduction of revenue resulting from the tax cuts, have also placed Bush's administration in a historic class of its own with respect to government borrowing. According to the Treasury Department, the forty-two presidents who held office between 1789 and 2000 borrowed a combined total of $1.01 trillion from foreign governments and financial institutions. But between 2001 and 2005 alone, the Bush White House borrowed $1.05 trillion, more than all of the previous presidencies combined. Having inherited the largest federal surplus in American history in 2001, he has turned it into the largest deficit ever -- with an even higher deficit, $423 billion, forecast for fiscal year 2006. Yet Bush -- sounding much like Herbert Hoover in 1930 predicting that "prosperity is just around the corner" -- insists that he will cut federal deficits in half by 2009, and that the best way to guarantee this would be to make permanent his tax cuts, which helped cause the deficit in the first place!

The rest of what remains of Bush's skimpy domestic agenda is either failed or failing -- a record unmatched since the presidency of Herbert Hoover. The No Child Left Behind educational-reform act has proved so unwieldy, draconian and poorly funded that several states -- including Utah, one of Bush's last remaining political strongholds -- have fought to opt out of it entirely. White House proposals for immigration reform and a guest-worker program have succeeded mainly in dividing pro-business Republicans (who want more low-wage immigrant workers) from paleo-conservatives fearful that hordes of Spanish-speaking newcomers will destroy American culture. The paleos' call for tougher anti-immigrant laws -- a return to the punitive spirit of exclusion that led to the notorious Immigration Act of 1924 that shut the door to immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe -- has in turn deeply alienated Hispanic voters from the Republican Party, badly undermining the GOP's hopes of using them to build a permanent national electoral majority. The recent pro-immigrant demonstrations, which drew millions of marchers nationwide, indicate how costly the Republican divide may prove.

The one noncorporate constituency to which Bush has consistently deferred is the Christian right, both in his selections for the federal bench and in his implications that he bases his policies on premillennialist, prophetic Christian doctrine. Previous presidents have regularly invoked the Almighty. McKinley is supposed to have fallen to his knees, seeking divine guidance about whether to take control of the Philippines in 1898, although the story may be apocryphal. But no president before Bush has allowed the press to disclose, through a close friend, his startling belief that he was ordained by God to lead the country. The White House's sectarian positions -- over stem-cell research, the teaching of pseudoscientific "intelligent design," global population control, the Terri Schiavo spectacle and more -- have led some to conclude that Bush has promoted the transformation of the GOP into what former Republican strategist Kevin Phillips calls "the first religious party in U.S. history."Bush's faith-based conception of his mission, which stands above and beyond reasoned inquiry, jibes well with his administration's pro-business dogma on global warming and other urgent environmental issues. While forcing federally funded agencies to remove from their Web sites scientific information about reproductive health and the effectiveness of condoms in combating HIV/AIDS, and while peremptorily overruling staff scientists at the Food and Drug Administration on making emergency contraception available over the counter, Bush officials have censored and suppressed research findings they don't like by the Environmental Protection Agency, the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Department of Agriculture. Far from being the conservative he said he was, Bush has blazed a radical new path as the first American president in history who is outwardly hostile to science -- dedicated, as a distinguished, bipartisan panel of educators and scientists (including forty-nine Nobel laureates) has declared, to "the distortion of scientific knowledge for partisan political ends."

The Bush White House's indifference to domestic problems and science alike culminated in the catastrophic responses to Hurricane Katrina. Scientists had long warned that global warming was intensifying hurricanes, but Bush ignored them -- much as he and his administration sloughed off warnings from the director of the National Hurricane Center before Katrina hit. Reorganized under the Department of Homeland Security, the once efficient Federal Emergency Management Agency turned out, under Bush, to have become a nest of cronyism and incompetence. During the months immediately after the storm, Bush traveled to New Orleans eight times to promise massive rebuilding aid from the federal government. On March 30th, however, Bush's Gulf Coast recovery coordinator admitted that it could take as long as twenty-five years for the city to recover.

Karl Rove has sometimes likened Bush to the imposing, no-nonsense President Andrew Jackson. Yet Jackson took measures to prevent those he called "the rich and powerful" from bending "the acts of government to their selfish purposes." Jackson also gained eternal renown by saving New Orleans from British invasion against terrible odds. Generations of Americans sang of Jackson's famous victory. In 1959, Johnny Horton's version of "The Battle of New Orleans" won the Grammy for best country & western performance. If anyone sings about George W. Bush and New Orleans, it will be a blues number.

* * * *

PRESIDENTIAL MISCONDUCT

Virtually every presidential administration dating back to George Washington's has faced charges of misconduct and threats of impeachment against the president or his civil officers. The alleged offenses have usually involved matters of personal misbehavior and corruption, notably the payoff scandals that plagued Cabinet officials who served presidents Harding and Ulysses S. Grant. But the charges have also included alleged usurpation of power by the president and serious criminal conduct that threatens constitutional government and the rule of law -- most notoriously, the charges that led to the impeachments of Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton, and to Richard Nixon's resignation.

Historians remain divided over the actual grievousness of many of these allegations and crimes. Scholars reasonably describe the graft and corruption around the Grant administration, for example, as gargantuan, including a kickback scandal that led to the resignation of Grant's secretary of war under the shadow of impeachment. Yet the scandals produced no indictments of Cabinet secretaries and only one of a White House aide, who was acquitted. By contrast, the most scandal-ridden administration in the modern era, apart from Nixon's, was Ronald Reagan's, now widely remembered through a haze of nostalgia as a paragon of virtue. A total of twenty-nine Reagan officials, including White House national security adviser Robert McFarlane and deputy chief of staff Michael Deaver, were convicted on charges stemming from the Iran-Contra affair, illegal lobbying and a looting scandal inside the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Three Cabinet officers -- HUD Secretary Samuel Pierce, Attorney General Edwin Meese and Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger -- left their posts under clouds of scandal. In contrast, not a single official in the Clinton administration was even indicted over his or her White House duties, despite repeated high-profile investigations and a successful, highly partisan impeachment drive.

The full report, of course, has yet to come on the Bush administration. Because Bush, unlike Reagan or Clinton, enjoys a fiercely partisan and loyal majority in Congress, his administration has been spared scrutiny. Yet that mighty advantage has not prevented the indictment of Vice President Dick Cheney's chief of staff, I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby, on charges stemming from an alleged major security breach in the Valerie Plame matter. (The last White House official of comparable standing to be indicted while still in office was Grant's personal secretary, in 1875.) It has not headed off the unprecedented scandal involving Larry Franklin, a high-ranking Defense Department official, who has pleaded guilty to divulging classified information to a foreign power while working at the Pentagon -- a crime against national security. It has not forestalled the arrest and indictment of Bush's top federal procurement official, David Safavian, and the continuing investigations into Safavian's intrigues with the disgraced Republican lobbyist Jack Abramoff, recently sentenced to nearly six years in prison -- investigations in which some prominent Republicans, including former Christian Coalition executive director Ralph Reed (and current GOP aspirant for lieutenant governor of Georgia) have already been implicated, and could well produce the largest congressional corruption scandal in American history. It has not dispelled the cloud of possible indictment that hangs over others of Bush's closest advisers.

History may ultimately hold Bush in the greatest contempt for expanding the powers of the presidency beyond the limits laid down by the U.S. Constitution. There has always been a tension over the constitutional roles of the three branches of the federal government. The Framers intended as much, as part of the system of checks and balances they expected would minimize tyranny. When Andrew Jackson took drastic measures against the nation's banking system, the Whig Senate censured him for conduct "dangerous to the liberties of the people." During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln's emergency decisions to suspend habeas corpus while Congress was out of session in 1861 and 1862 has led some Americans, to this day, to regard him as a despot. Richard Nixon's conduct of the war in Southeast Asia and his covert domestic-surveillance programs prompted Congress to pass new statutes regulating executive power.

By contrast, the Bush administration -- in seeking to restore what Cheney, a Nixon administration veteran, has called "the legitimate authority of the presidency" -- threatens to overturn the Framers' healthy tension in favor of presidential absolutism. Armed with legal findings by his attorney general (and personal lawyer) Alberto Gonzales, the Bush White House has declared that the president's powers as commander in chief in wartime are limitless. No previous wartime president has come close to making so grandiose a claim. More specifically, this administration has asserted that the president is perfectly free to violate federal laws on such matters as domestic surveillance and the torture of detainees. When Congress has passed legislation to limit those assertions, Bush has resorted to issuing constitutionally dubious "signing statements," which declare, by fiat, how he will interpret and execute the law in question, even when that interpretation flagrantly violates the will of Congress. Earlier presidents, including Jackson, raised hackles by offering their own view of the Constitution in order to justify vetoing congressional acts. Bush doesn't bother with that: He signs the legislation (eliminating any risk that Congress will overturn a veto), and then governs how he pleases -- using the signing statements as if they were line-item vetoes. In those instances when Bush's violations of federal law have come to light, as over domestic surveillance, the White House has devised a novel solution: Stonewall any investigation into the violations and bid a compliant Congress simply to rewrite the laws.Bush's alarmingly aberrant take on the Constitution is ironic. One need go back in the record less than a decade to find prominent Republicans railing against far more minor presidential legal infractions as precursors to all-out totalitarianism. "I will have no part in the creation of a constitutional double-standard to benefit the president," Sen. Bill Frist declared of Bill Clinton's efforts to conceal an illicit sexual liaison. "No man is above the law, and no man is below the law -- that's the principle that we all hold very dear in this country," Rep. Tom DeLay asserted. "The rule of law protects you and it protects me from the midnight fire on our roof or the 3 a.m. knock on our door," warned Rep. Henry Hyde, one of Clinton's chief accusers. In the face of Bush's more definitive dismissal of federal law, the silence from these quarters is deafening.

The president's defenders stoutly contend that war-time conditions fully justify Bush's actions. And as Lincoln showed during the Civil War, there may be times of military emergency where the executive believes it imperative to take immediate, highly irregular, even unconstitutional steps. "I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful," Lincoln wrote in 1864, "by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the Constitution, through the preservation of the nation." Bush seems to think that, since 9/11, he has been placed, by the grace of God, in the same kind of situation Lincoln faced. But Lincoln, under pressure of daily combat on American soil against fellow Americans, did not operate in secret, as Bush has. He did not claim, as Bush has, that his emergency actions were wholly regular and constitutional as well as necessary; Lincoln sought and received Congressional authorization for his suspension of habeas corpus in 1863. Nor did Lincoln act under the amorphous cover of a "war on terror" -- a war against a tactic, not a specific nation or political entity, which could last as long as any president deems the tactic a threat to national security. Lincoln's exceptional measures were intended to survive only as long as the Confederacy was in rebellion. Bush's could be extended indefinitely, as the president sees fit, permanently endangering rights and liberties guaranteed by the Constitution to the citizenry.

* * * *

Much as Bush still enjoys support from those who believe he can do no wrong, he now suffers opposition from liberals who believe he can do no right. Many of these liberals are in the awkward position of having supported Bush in the past, while offering little coherent as an alternative to Bush's policies now. Yet it is difficult to see how this will benefit Bush's reputation in history.

The president came to office calling himself "a uniter, not a divider" and promising to soften the acrimonious tone in Washington. He has had two enormous opportunities to fulfill those pledges: first, in the noisy aftermath of his controversial election in 2000, and, even more, after the attacks of September 11th, when the nation pulled behind him as it has supported no other president in living memory. Yet under both sets of historically unprecedented circumstances, Bush has chosen to act in ways that have left the country less united and more divided, less conciliatory and more acrimonious -- much like James Buchanan, Andrew Johnson and Herbert Hoover before him. And, like those three predecessors, Bush has done so in the service of a rigid ideology that permits no deviation and refuses to adjust to changing realities. Buchanan failed the test of Southern secession, Johnson failed in the face of Reconstruction, and Hoover failed in the face of the Great Depression. Bush has failed to confront his own failures in both domestic and international affairs, above all in his ill-conceived responses to radical Islamic terrorism. Having confused steely resolve with what Ralph Waldo Emerson called "a foolish consistency . . . adored by little statesmen," Bush has become entangled in tragedies of his own making, compounding those visited upon the country by outside forces.

No historian can responsibly predict the future with absolute certainty. There are too many imponderables still to come in the two and a half years left in Bush's presidency to know exactly how it will look in 2009, let alone in 2059. There have been presidents -- Harry Truman was one -- who have left office in seeming disgrace, only to rebound in the estimates of later scholars. But so far the facts are not shaping up propitiously for George W. Bush. He still does his best to deny it. Having waved away the lessons of history in the making of his decisions, the present-minded Bush doesn't seem to be concerned about his place in history. "History. We won't know," he told the journalist Bob Woodward in 2003. "We'll all be dead."

Another president once explained that the judgments of history cannot be defied or dismissed, even by a president. "Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history," said Abraham Lincoln. "We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation."

(From RS 999, May 4, 2006)

Flashback: Bush in '99 -- We Warned You!

Lie by Lie: The Mother Jones Iraq War Timeline (8/1/90 - 2/14/08)

In this timeline, we've assembled the history of the Iraq War to create a resource we hope will help resolve open questions of the Bush era. What did our leaders know and when did they know it? And, perhaps just as important, what red flags did we miss, and how could we have missed them? This is the third installment of the timeline, with a focus on Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo, and torture in a time of terror.

False Pretenses

Following 9/11, President Bush and seven top officials of his administration waged a carefully orchestrated campaign of misinformation about the threat posed by Saddam Hussein's Iraq.

President George W. Bush and seven of his administration's top officials, including Vice President Dick Cheney, National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, made at least 935 false statements in the two years following September 11, 2001, about the national security threat posed by Saddam Hussein's Iraq. Nearly five years after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, an exhaustive examination of the record shows that the statements were part of an orchestrated campaign that effectively galvanized public opinion and, in the process, led the nation to war under decidedly false pretenses.

On at least 532 separate occasions (in speeches, briefings, interviews, testimony, and the like), Bush and these three key officials, along with Secretary of State Colin Powell, Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, and White House press secretaries Ari Fleischer and Scott McClellan, stated unequivocally that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction (or was trying to produce or obtain them), links to Al Qaeda, or both. This concerted effort was the underpinning of the Bush administration's case for war.

It is now beyond dispute that Iraq did not possess any weapons of mass destruction or have meaningful ties to Al Qaeda. This was the conclusion of numerous bipartisan government investigations, including those by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (2004 and 2006), the 9/11 Commission, and the multinational Iraq Survey Group, whose "Duelfer Report" established that Saddam Hussein had terminated Iraq's nuclear program in 1991 and made little effort to restart it.

In short, the Bush administration led the nation to war on the basis of erroneous information that it methodically propagated and that culminated in military action against Iraq on March 19, 2003. Not surprisingly, the officials with the most opportunities to make speeches, grant media interviews, and otherwise frame the public debate also made the most false statements, according to this first-ever analysis of the entire body of prewar rhetoric.

President Bush, for example, made 232 false statements about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and another 28 false statements about Iraq's links to Al Qaeda. Secretary of State Powell had the second-highest total in the two-year period, with 244 false statements about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and 10 about Iraq's links to Al Qaeda. Rumsfeld and Fleischer each made 109 false statements, followed by Wolfowitz (with 85), Rice (with 56), Cheney (with 48), and McClellan (with 14).

The massive database at the heart of this project juxtaposes what President Bush and these seven top officials were saying for public consumption against what was known, or should have been known, on a day-to-day basis. This fully searchable database includes the public statements, drawn from both primary sources (such as official transcripts) and secondary sources (chiefly major news organizations) over the two years beginning on September 11, 2001. It also interlaces relevant information from more than 25 government reports, books, articles, speeches, and interviews.

Consider, for example, these false public statements made in the run-up to war:

- On August 26, 2002, in an address to the national convention of the Veteran of Foreign Wars, Cheney flatly declared: "Simply stated, there is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction. There is no doubt he is amassing them to use against our friends, against our allies, and against us." In fact, former CIA Director George Tenet later recalled, Cheney's assertions went well beyond his agency's assessments at the time. Another CIA official, referring to the same speech, told journalist Ron Suskind, "Our reaction was, 'Where is he getting this stuff from?' "

- In the closing days of September 2002, with a congressional vote fast approaching on authorizing the use of military force in Iraq, Bush told the nation in his weekly radio address: "The Iraqi regime possesses biological and chemical weapons, is rebuilding the facilities to make more and, according to the British government, could launch a biological or chemical attack in as little as 45 minutes after the order is given. . . . This regime is seeking a nuclear bomb, and with fissile material could build one within a year." A few days later, similar findings were also included in a much-hurried National Intelligence Estimate on Iraq's weapons of mass destruction — an analysis that hadn't been done in years, as the intelligence community had deemed it unnecessary and the White House hadn't requested it.

- In July 2002, Rumsfeld had a one-word answer for reporters who asked whether Iraq had relationships with Al Qaeda terrorists: "Sure." In fact, an assessment issued that same month by the Defense Intelligence Agency (and confirmed weeks later by CIA Director Tenet) found an absence of "compelling evidence demonstrating direct cooperation between the government of Iraq and Al Qaeda." What's more, an earlier DIA assessment said that "the nature of the regime's relationship with Al Qaeda is unclear."

- On May 29, 2003, in an interview with Polish TV, President Bush declared: "We found the weapons of mass destruction. We found biological laboratories." But as journalist Bob Woodward reported in State of Denial, days earlier a team of civilian experts dispatched to examine the two mobile labs found in Iraq had concluded in a field report that the labs were not for biological weapons. The team's final report, completed the following month, concluded that the labs had probably been used to manufacture hydrogen for weather balloons.

- On January 28, 2003, in his annual State of the Union address, Bush asserted: "The British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa. Our intelligence sources tell us that he has attempted to purchase high-strength aluminum tubes suitable for nuclear weapons production." Two weeks earlier, an analyst with the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research sent an email to colleagues in the intelligence community laying out why he believed the uranium-purchase agreement "probably is a hoax."

- On February 5, 2003, in an address to the United Nations Security Council, Powell said: "What we're giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence. I will cite some examples, and these are from human sources." As it turned out, however, two of the main human sources to which Powell referred had provided false information. One was an Iraqi con artist, code-named "Curveball," whom American intelligence officials were dubious about and in fact had never even spoken to. The other was an Al Qaeda detainee, Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi, who had reportedly been sent to Eqypt by the CIA and tortured and who later recanted the information he had provided. Libi told the CIA in January 2004 that he had "decided he would fabricate any information interrogators wanted in order to gain better treatment and avoid being handed over to [a foreign government]."

The false statements dramatically increased in August 2002, with congressional consideration of a war resolution, then escalated through the mid-term elections and spiked even higher from January 2003 to the eve of the invasion.

It was during those critical weeks in early 2003 that the president delivered his State of the Union address and Powell delivered his memorable U.N. presentation. For all 935 false statements, including when and where they occurred, go to the search page for this project; the methodology used for this analysis is explained here.

In addition to their patently false pronouncements, Bush and these seven top officials also made hundreds of other statements in the two years after 9/11 in which they implied that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction or links to Al Qaeda. Other administration higher-ups, joined by Pentagon officials and Republican leaders in Congress, also routinely sounded false war alarms in the Washington echo chamber.

The cumulative effect of these false statements — amplified by thousands of news stories and broadcasts — was massive, with the media coverage creating an almost impenetrable din for several critical months in the run-up to war. Some journalists — indeed, even some entire news organizations — have since acknowledged that their coverage during those prewar months was far too deferential and uncritical. These mea culpas notwithstanding, much of the wall-to-wall media coverage provided additional, "independent" validation of the Bush administration's false statements about Iraq.

The "ground truth" of the Iraq war itself eventually forced the president to backpedal, albeit grudgingly. In a 2004 appearance on NBC's Meet the Press, for example, Bush acknowledged that no weapons of mass destruction had been found in Iraq. And on December 18, 2005, with his approval ratings on the decline, Bush told the nation in a Sunday-night address from the Oval Office: "It is true that Saddam Hussein had a history of pursuing and using weapons of mass destruction. It is true that he systematically concealed those programs, and blocked the work of U.N. weapons inspectors. It is true that many nations believed that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction. But much of the intelligence turned out to be wrong. As your president, I am responsible for the decision to go into Iraq. Yet it was right to remove Saddam Hussein from power."

Bush stopped short, however, of admitting error or poor judgment; instead, his administration repeatedly attributed the stark disparity between its prewar public statements and the actual "ground truth" regarding the threat posed by Iraq to poor intelligence from a Who's Who of domestic agencies.

On the other hand, a growing number of critics, including a parade of former government officials, have publicly — and in some cases vociferously — accused the president and his inner circle of ignoring or distorting the available intelligence. In the end, these critics say, it was the calculated drumbeat of false information and public pronouncements that ultimately misled the American people and this nation's allies on their way to war.

Bush and the top officials of his administration have so far largely avoided the harsh, sustained glare of formal scrutiny about their personal responsibility for the litany of repeated, false statements in the run-up to the war in Iraq. There has been no congressional investigation, for example, into what exactly was going on inside the Bush White House in that period. Congressional oversight has focused almost entirely on the quality of the U.S. government's pre-war intelligence — not the judgment, public statements, or public accountability of its highest officials. And, of course, only four of the officials — Powell, Rice, Rumsfeld, and Wolfowitz — have testified before Congress about Iraq.

Short of such review, this project provides a heretofore unavailable framework for examining how the U.S. war in Iraq came to pass. Clearly, it calls into question the repeated assertions of Bush administration officials that they were the unwitting victims of bad intelligence.

Above all, the 935 false statements painstakingly presented here finally help to answer two all-too-familiar questions as they apply to Bush and his top advisers: What did they know, and when did they know it?

Published on Sunday, January 21, 2001 in the Philadelphia Inquirer | |

| Inauguration Protests Largest Since Nixon in 1973 | |

| by Angela Couloumbis | |

| WASHINGTON - Thousands of activists from across the country marched down the rain-slick streets of the capital yesterday, waving signs, chanting slogans, and maneuvering for spots at key inaugural ceremonies for a chance to denounce President Bush. Organizers of permitted demonstrations along the inaugural parade route said more than 20,000 protesters had gathered in downtown Washington for mostly orderly rallies; police declined to give crowd estimates. By late afternoon, police had arrested about a dozen protesters, charging most with disorderly conduct or other misdemeanors. One was charged with assault with a deadly weapon after slashing tires and trying to assault an officer, police said. Some protesters said they were clubbed by police, but police denied the allegations. A few officers were hurt after protesters threw bottles at them, but none of the injuries required hospitalization, Deputy Police Chief Terry Gainer said. Protesters clashed briefly with police at a few flash points, while Bush remained inside his car for most of the parade up a soggy, cold Pennsylvania Avenue. The motorcade sped up as it reached some protests, causing Secret Service agents to break into a run alongside the vehicles. At one point, police stopped the motorcade for five minutes because of the protests. A couple of protesters threw bottles before Bush's limousine arrived, and one hurled an egg that landed near the new Cadillac, which featured puncture-proof tires and six-inch-thick bulletproof glass. The President left the car to walk only after he reached a secure zone near the White House that held inauguration ticket-holders. For the most part, activists called yesterday's protests a success, saying they had managed to get their message across despite some of the most stringent security measures taken by police at a presidential inauguration. More than 10,000 officers from 16 law-enforcement agencies, including the Secret Service, the U.S. Park Police, and the District of Columbia's police force lined the streets beginning at dawn. "Bush may be president, but I know that when he goes to sit in the Oval Office for the first time, he's going to look out the window, and see and hear us," said Bob Rogers, a founder and organizer of yesterday's Voter March, a nonpartisan group protesting voter disenfranchisement and championing reforms to the Electoral College. "I don't want to personalize this," Rogers said of Bush. "I'm not going to scream 'Hail to the thief,' as others may do. But I will say, 'Respect the presidency,' because during this election, it was not respected." Others were not so diplomatic. At Freedom Plaza, a protest space along the parade route at 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, thousands of protesters held up signs calling Bush such epithets as "thief" and "pig." When Bush's motorcade passed, they booed and jeered and yelled obscenities. Some held up middle fingers. And before the motorcade sped by, some activists upset over the lines at security checkpoints turned toward Bush's supporters in bleachers about 20 feet away, yelling "shame," and "ignorance is bliss," and making obscene gestures. "It bothers me a little bit that they're screaming at us," said David Yiu, a Bush supporter from New York City who had a bleacher seat at Freedom Plaza. "I believe that everyone has the right to express a point of view. But you can express your point of view by calling your senator or your congressman. This is America. If you don't like something, you can change it." Laura Brightman of Brooklyn, N.Y., did not share that sentiment. Brightman, who joined about 2,000 people for a "Shadow Convention" led by the Rev. Al Sharpton, said the legal wrangling that followed the election proved that any honest attempt at change would be quashed by politics. "We were sold out," she said, as others around her chanted, "No justice, no peace." "And when we tried to get justice [from the Supreme Court] we were sold again. The election was stolen." At the Supreme Court building, Rudy Arredondo of Takoma Park, Md., put it this way: "Bush is a Supreme Court appointee. In my eyes, and in my children's eyes, he will never be a legitimate president." Hundreds of Bush supporters had gathered earlier at the building to sing "God Bless America." "Bush is a legitimate president," said Kevin Conner of the National Patriots March, a pro-Bush group that wanted to provide a counterpoint to yesterday's protests. "We want to send that message loud and clear. We are not going to sit by and fume and get mad when we read stories about left-wing radicals. We are going to stand up to it and be active." Though the Christian Defense Coalition rallied for Bush along Pennsylvania Avenue yesterday, Conner's group of about 300 people was in the minority. Cheri Honkala, director of the Kensington Welfare Rights Union, a Philadelphia advocacy group, traveled to Washington to march to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to protest what she said were injustices against the poor. Although her group did not have a permit to march, their action was successful and her group's message was heard, she said. "People will go back to their states and continue to be homeless, but they feel rejuvenated," Honkala said, adding that her group had set up a tent made out of American flags and blankets in front of the Health and Human Services Department. "Being here today was very important for them." The Other Lies of George BushBy David Corn This article appeared in the October 13, 2003 edition of The Nation. September 25, 2003...But Bush's truth-defying crusade for war did not mark a shift for him. Throughout his campaign for the presidency and his years in the White House, Bush has mugged the truth in many other areas to advance his agenda. Lying has been one of the essential tools of his presidency. To call the forty-third President of the United States a prevaricator is not an exercise of opinion, not an inflammatory talk-radio device. Rather, it is backed up by an all-too-extensive record of self-serving falsifications. While politicians are often derided as liars, this charge should be particularly stinging for Bush. During the campaign of 2000, he pitched himself as a candidate who could "restore" honor and integrity to an Oval Office stained by the misdeeds and falsehoods of his predecessor. To brand Bush a liar is to negate what he and his supporters declared was his most basic and most important qualification for the job. His claims about the war in Iraq have led more of his foes and more pundits to accuse him of lying to the public. The list of his misrepresentations, though, is far longer than the lengthy list of dubious statements Bush employed--and keeps on employing--to justify his invasion and occupation of Iraq. Here then is a partial--a quite partial--account of the other lies of George W. Bush. Tax Cuts Bush's crusade for tax cuts is the domestic policy matter that has spawned the most misrepresentations from his camp. On the 2000 campaign trail, he sold his success as a "tax-cutting person" by hailing cuts he passed in Texas while governor. But Bush did not tell the full story of his 1997 tax plan. His proposal called for cutting property taxes. But what he didn't mention is that it also included an attempt to boost the sales tax and to implement a new business tax. Nor did he note that his full package had not been accepted by the state legislature. Instead, the lawmakers passed a $1 billion reduction in property taxes. And these tax cuts turned out to be a sham. After they kicked in, school districts across the state boosted local tax rates to compensate for the loss of revenue. A 1999 Dallas Morning News analysis found that "many [taxpayers] are still paying as much as they did in 1997, or more." Republican Lieutenant Governor Rick Perry called the cuts "rather illusory." One of Bush's biggest tax-cut whoppers came when he stated, during the presidential campaign, "The vast majority of my [proposed] tax cuts go to the bottom end of the spectrum." That estimate was wildly at odds with analyses of where the money would really go. A report by Citizens for Tax Justice, a liberal outfit that specializes in distribution analysis, figured that 42.6 percent of Bush's $1.6 trillion tax package would end up in the pockets of the top 1 percent of earners. The lowest 60 percent would net 12.6 percent. The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, ABC News and NBC News all reported that Bush's package produced the results CTJ calculated. To deal with the criticism that his plan was a boon for millionaires, Bush devised an imaginary friend--a mythical single waitress who was supporting two children on an income of $22,000, and he talked about her often. He said he wanted to remove the tax-code barriers that kept this waitress from reaching the middle class, and he insisted that if his tax cuts were passed, "she will pay no income taxes at all." But when Time asked the accounting firm of Deloitte & Touche to analyze precisely how Bush's waitress-mom would be affected by his tax package, the firm reported that she would not see any benefit because she already had no income-tax liability. As he sold his tax cuts from the White House, Bush maintained in 2001 that with his plan, "the greatest percentage of tax relief goes to the people at the bottom end of the ladder." This was trickery--technically true only because low-income earners pay so little income tax to begin with. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities put it, "a two-parent family of four with income of $26,000 would indeed have its income taxes eliminated under the Bush plan, which is being portrayed as a 100 percent reduction in taxes." But here was the punch line: The family owed only $20 in income taxes under the existing law. Its overall tax bill (including payroll and excise taxes), though, was $2,500. So that twenty bucks represented less than 1 percent of its tax burden. Bush's "greatest percentage" line was meaningless in the real world, where people paid their bills with money, not percentages. Bush also claimed his tax plan--by eliminating the estate tax, at a cost of $300 billion--would "keep family farms in the family." But, as the New York Times reported, farm-industry experts could not point to a single case of a family losing a farm because of estate taxes. Asked about this, White House press secretary Ari Fleischer said, "If you abolish the death tax, people won't have to hire all those planners to help them keep the land that's rightfully theirs." Caught in a $300 billion lie, the White House was now saying the reason to abolish the tax--a move that would be a blessing to the richest 2 percent of Americans--was to spare farmers the pain in the ass of estate planning. Bush's lies did not hinder him. They helped him win the first tax-cut fight--and, then, the tax-cut battle of 2003. When his second set of supersized tax cuts was assailed for being tilted toward the rich, he claimed, "Ninety-two million Americans will keep an average of $1,083 more of their own money." The Tax Policy Center of the Brookings Institution and the Urban Institute found that, contrary to Bush's assertion, nearly 80 percent of tax filers would receive less than $1,083, and almost half would pocket less than $100. The truly average taxpayers--those in the middle of the income range--would receive $265. Bush was using the word "average" in a flimflam fashion. To concoct the misleading $1,083 figure, the Administration took the large dollar amounts high-income taxpayers would receive and added that to the modest, small or nonexistent reductions other taxpayers would get--and then used this total to calculate an average gain. His claim was akin to saying that if a street had nine households led by unemployed individuals but one with an earner making a million dollars, the average income of the families on the block would be $100,000. The radical Wall Street Journal reported, "Overall, the gains from the taxes are weighted toward upper-income taxpayers." |

Complete 911 Timeline

Bush's Actions on 9/11

DUBYA ATTENDS OPEC APEC CONFERENCE IN AUSTRIA AUSTRALIA, MAKES ASS OF SELF

SYDNEY, Australia, Sep. 7, 2007 -- By all accounts, Dubya's appearance at the APEC Business Summit in Sydney, Australia was terribly entertaining, in the strictest sense of that expression.

SYDNEY, Australia, Sep. 7, 2007 -- By all accounts, Dubya's appearance at the APEC Business Summit in Sydney, Australia was terribly entertaining, in the strictest sense of that expression.

Dubya started his speech off by getting the name of the organization whose event he was attending wrong:

"Uh, Mr. Prime Minister, thank you for your introduction. Thank you for being such a -- uhh, a fine host for the OPEC summit." ![]()

Although the official White House transcript doesn't record it this way, Dubya next referred to Australian Prime Minister John Howard visiting Austrian troops:

"We're givin' this young democracy the chance. It's in our interest to do so -- because, as John Howard accurately noted when he went to thank the Austrian troops there last year." ![]()

As usually happens in nearly all of Dubya's speeches, the topic of terrorism came up, and Dubya had occasion to mention the terror organization known as Jemaah Islamiyah, or JI... or Jemai-Islai-a-may-ah if you're Dubya:

"[One of] the two most dangerous terrorist networks in this region are a group called Jemai-Islai-a-may-ah, or JI."Another exit strategy fails:

Along with stumbling through the pronunciation of words like Canberra and Kuala Lumpur, and sounding pretty tongue-tied in general, Dubya managed to conclude the appearance with a repeat performance of his failed exit strategy incident (Beijing, 2005) by marching off to the side of the stage -- where there was no exit -- only to be called back to exit from the front of the stage by Howard (shown on the left).

Along with stumbling through the pronunciation of words like Canberra and Kuala Lumpur, and sounding pretty tongue-tied in general, Dubya managed to conclude the appearance with a repeat performance of his failed exit strategy incident (Beijing, 2005) by marching off to the side of the stage -- where there was no exit -- only to be called back to exit from the front of the stage by Howard (shown on the left). Perhaps the crowning image of the entire event, though, was the official summit photograph, for which all the APEC leaders were asked to raise their right hands in salute (shown above).

Dubya used his other right hand.

No comments:

Post a Comment