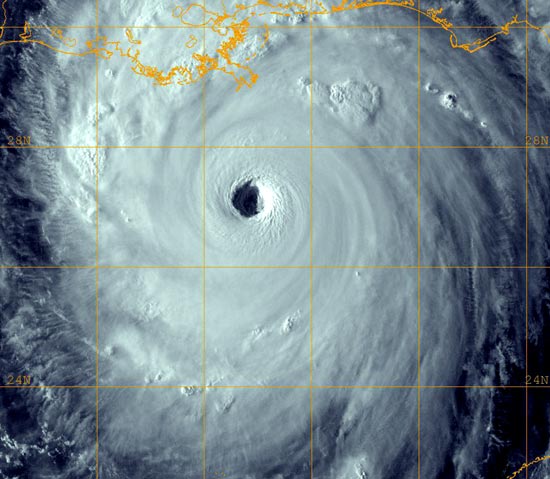

New Orleans levees remain worry

by Frank James

I just watched Homeland Security Sec. Michael Chertoff's brief press conference at Andrews Air Force base just before he got on a plane to head to the Gulf Coast region to check in on preparations for Hurricane Gustav.

The secretary, a very nice man, said the levees are stronger than they were before Hurricane Katrina. Chertoff should doublecheck that information.

The reporting I've read indicates that the levees are not generally and absolutely stronger. True, some levees have been strengthened and rebuilt after they failed.

But there've been questions about the rebuilding efforts that reconstructed levees that failed after Katrina.

There's also been seepage under a few of the levees that has confounded the Army Corps of Engineers.

Some of the levees that held up under Katrina are among those that experts are most worried about.

Here's a story from New Orleans's Times-Picayune newspaper from April 17, 2008:

Despite withstanding Hurricane Katrina and being poised to.

become the area's first levee to reach the vaunted 100-year storm elevation, the

East Jefferson lakefront levee might not be adequate and may need to be totally

rebuilt or substantially enlarged.

Stunning new data spit out by a complex geotechnical

computer model has concluded that lake levees in East Jefferson and St. Charles

Parish could be at risk for catastrophic failure.

Though Army Corps of Engineers officials said some experts

doubt the accuracy of the new analysis, the agency intends to identify and

implement solutions -- which could range from entirely rebuilding the levees to

constructing a huge rock jetty in front of them.

"Our new method of analysis has given us (data) that we

don't intend to ignore," said Lt. Col. Murray Starkel, deputy commander of the

corps' New Orleans District.

Because the corps is under the gun to provide an improved

hurricane protection system by 2011, officials said they can't wait for the

results of additional studies that might ultimately debunk this new finding of

the "Spencer's method" analysis.

"There will come a point at which we go forward with

(contracts), even if they produce an overly conservative design," said

geotechnical engineer John Grieshaber, technical support chief for the corps'

Hurricane Protection Office.

"We will award contracts to meet that 2011 date, and if we

find out later that we can do with a less conservative design, we can modify a

contract in the field," he said.

Design standards updated

The computer-generated

data, which blindsided even those engineers overseeing planned improvements to

the region's hurricane protection system, are the result of applying more

conservative design standards adopted since Katrina.

Key to that corps effort to ratchet up reliability, complex

computer software was specially adapted over the past year that enabled the

Spencer's analysis to identify any type of failure that could possibly occur in

tricky south Louisiana soils.

As recently as January, engineers overseeing planned

improvements to the East Jefferson lakefront predicted that it would be the

first to attain the new elevations needed to help provide a stepped-up 100-year

level of storm surge protection by 2011.

But the very next month, the Spencer's software began

unspooling the news that it had identified a failure potential not detected by

previous computer analyses in the Lake Pontchartrain levees of East Jefferson

and St. Charles Parish.

"No, we absolutely did not expect this result," Rich

Varuso, geotechnical chief for the district's engineering division, said of the

geometry-based calculations that resulted

Now, keep in mind, this is a levee that didn't fail during Katrina. What about a levee that did fail. That should be unquestionably stronger, right? Think again.

Here's a story from the May 30, 2008 Times-Picayune:

Water persistently seeping out of the 17th Street Canal near

the repaired levee and floodwall indicates serious flaws in the design, not only of that levee section but of much of the multibillion-dollar 100-year hurricane protection for the region, a California engineering expert and outspoken critic of the Army Corps of Engineers has repeatedly charged.

For months, corps engineers have said the water puddling

outside the levee near the infamous 17th Street Canal breach does not threaten the levee or repaired floodwalls.

Now, on the eve of the third hurricane season since Katrina, the local levee district wants to know who is right, and it has called in an independent team of engineers to figure it out.

"We've got to get to the bottom of these issues . . . starting with the seepage at the 17th Street Canal," said Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East commissioner Tom Jackson of Metairie, a retired civil engineer and a former president of the American Society of Civil Engineers."(University of California-Berkeley civil engineering professor Bob) Bea says one thing, the corps says another and we have an obligation to the public to find out who's right and who's wrong," Jackson said. "If the challenges are valid, the corps needs to address them. And if they're not, they can be dismissed."

--- Independent review planned ---

Jackson, levee authority President Tim Doody of St. Bernard and commissioner John Barry of New Orleans began discussing the need for independent peer review late last week. On Wednesday, Doody said he

invited the corps to join in that undertaking, an offer he said was readily accepted.

"We are embracing the idea of peer review," said Karen

Durham-Aguilera, director of the corps' Task Force Hope mission of overseeing repairs, rebuilding and improvements to the federal flood defense system brought to its knees by Hurricane Katrina.

Levee commissioners anticipate asking the National Academy of Engineering, or some other group independent of the corps

and Bea, to provide expertise about the condition of floodwalls along the 17th Street Canal and the source of seepage along the canal's eastern side. Corps engineers have said for months that they do not believe the small but persistent seepage is cause for alarm and is likely just water seeping into the levee through the sheets of steel piling used to repair the breach that occurred during Katrina.

"We continually monitor, test and watch . . . and we haven't

seen anything to make us think that isn't the case," Durham-Aguilera said. "But I think it's now valid to ask if there is a bigger issue . . . and we're doing that (through) the peer review process."

Bea rests his case against the system on multiple grounds of improper design, dangerous safety margins and flawed assumptions, most of which have been pinpointed by three post-Katrina forensic investigations -- including a Berkeley-based probe that Bea helped

co-lead for the National Science Foundation.

But Bea has also opined since late last fall that he has done subsequent analyses using information not previously available. And he says that work proves there are extensive underseepage problems that put many levees and floodwalls at greater risk than previously thought.

--- Working with victims ---

Bea, hired by a legal team representing thousands of Katrina victims seeking to collect damages from the corps in federal court, thinks underseepage is responsible for the water that continues to recur near the repaired breach in the canal's east wall, despite the corps' best efforts to dig up the area, remove rubble to eliminate seepage paths and repack with good clay.

Bea said his latest work on the 17th Street Canal, where he had access to corps' pressure readings taken in the subterranean marsh layers beneath the levees, showed an intimate and dangerous connection between water rising in the canal and, simultaneously, water rising so quickly under the levees that it destabilized them.

As a result, he said, the rising water table creates "uplift pressures" able to blow out or destabilize the levee and trigger a failure.

"The only way to keep that from happening there is to drive sheet piles so deep that the water can't seep into the adjacent levee, and the corps didn't do that," he said.

If the Army Corps of Engineers is wrong, and we all know they've been wrong before, and with New Orleans looking like it may take a more direct hit than with Gustav than it did during Katrina, there's a possibility we may even see more levee failures.

Posted by Frank James on August 31, 2008 10:39 AM

Joints are sealed outside, officials say

By Chris Kirkham

"You had a lot of work being done to get things up to snuff after Hurricane Katrina," said Maj. Timothy Kurgan, chief public affairs officer for the Corps' New Orleans district. "I don't want people thinking there's just a bunch of newspaper inside this wall, and that's the only thing keeping water out."

In order to prevent cracking in the floodwalls due to temperature change, walls are divided into separate panels with a half-inch gap in between.

A series of barriers are placed in the gaps to ensure floodwater or other debris does not seep inside. The most important barrier is a thick rubber "waterstop" that runs vertically from the top to the bottom of the floodwall gap and is anchored into the concrete foundation.

The waterstop is in the middle of the floodwall, and other rubber material fills the gap on both the front and back side of the floodwall. That material is sealed again on the outside.

Corps officials said Friday that three panel gaps in a flood wall near the Paris Road bridge in New Orleans, near the St. Bernard Parish line, were plugged with newspaper instead of rubber in May 2006, as an "expedient" method to do minor repairs the year after Katrina. Those three gaps were the only ones where such a method was used, Kurgan said.

"It's not the preferred technique," he said.

Because the waterstop is in place, and because the outside of the newspaper filling was sealed, the risk of leaking is minimal, he said. Several engineers pointed to the black rubber filling being installed on one of the Harvey Canal floodwall gaps.

Corps officials said it used its own hired workers in 2006 to put in the newspaper filling, not a contractor.

. . . . . . .

Chris Kirkham can be reached at ckirkham@timespicayune.com or (504) 826-3786.

![Ice palace at the St. Paul Winter Carnival, St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.[Credits : © Phillip M. James from TSW—CLICK/Chicago] Ice palace at the St. Paul Winter Carnival, St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.[Credits : © Phillip M. James from TSW—CLICK/Chicago]](http://media-2.web.britannica.com/eb-media/66/60566-003-322BE2E6.gif)