Next Victim of Turmoil May Be Your Salary

It is possible, for the first time in weeks, to imagine that the credit crisis may be about to ease. But one of the big lessons of the last year has been not to underestimate the severity of the economy’s problems. Those problems are not just about housing or Wall Street.

What, then, will the next stage of the downturn be about? It is likely to revolve around the worst slump in worker pay since — you knew this was coming — the Great Depression. This slump won’t be anywhere near as bad as the one during the Depression, but it also won’t be like anything the country has experienced in a long time.

Income for the median household — the one in the dead middle of the income distribution — will probably be lower in 2010 than it was, amazingly enough, a full decade earlier. That hasn’t happened since the 1930s. Already, median pay today is slightly lower than it was in 2000, and by 2010, could end up more than 5 percent lower than its old peak.

If you look back at poll results over the last few decades, you will see that nothing predicts the public mood quite like income growth.

When incomes are growing at a good clip, as they were in the mid-1980s and late ’90s, Americans are upbeat. When incomes stagnate, as they did in the early ’80s, early ’90s and in the last several years, people get worried about the state of the country. In the latest New York Times/CBS News poll, 89 percent of respondents said that the country had “pretty seriously gotten off on the wrong track,” a record high.

So it’s reasonable to expect that the great pay slump of the early 21st century is going to have a big effect on the next several years. Falling pay will weigh on living standards, consumer spending and economic growth and will help set the political atmosphere that awaits the next president.

•

The events of the last several weeks have removed any serious doubt that the economy is in a recession. In a recession, businesses cut back on their workers’ hours, hand out raises that don’t keep pace with inflation and often skip paying bonuses. These cuts in hours and pay are the main way that a downturn affects families, because only a small share of workers actually lose their jobs.

As the chart [at the top of] this column makes clear, every recent recession has brought an effective pay cut of somewhere between 3 and 7 percent for the typical family. The drop typically happens over a period of about three years, lasting longer than the recession officially does, as pay fails to keep up with inflation.

The recent turmoil — the freezing up of credit markets, the fall in stock markets, the acceleration of layoffs — has made it unlikely that the coming recession will be a particularly mild one.

“The biggest hit will be in 2009,” Nariman Behravesh, the chief economist of Global Insight, a research and forecasting firm, told me, “and it probably won’t be until 2011 until we see any kind of pay gains.”

What will make this recession different, no matter how deep or shallow it is, is that it’s following an expansion in which most families received little or no raise. The median household made $50,200 last year, slightly less than the $50,600 that the equivalent household earned in 2000, according to the Census Bureau. That’s the first time on record that income failed to set a new record in an economic expansion.

Why has it happened? There is no single cause.

Medical costs have risen rapidly, which means that health insurance premiums take up a bigger chunk of workers’ paychecks than they used to. Some of this money goes to good use; it pays for treatments that weren’t available even a few years ago. But some of it, the part that disappears into the inefficient American health care system, is clearly wasted.

And in the last couple of years, the value of the typical worker’s benefits package has stopped growing. Since 2005, benefits packages have become slightly smaller, notes Jared Bernstein of the Economic Policy Institute. So health benefits can’t come close to explaining the recent pay stagnation.

The bigger factors are probably some combination of the following: new technologies, global trade, slowing gains in educational attainment, the rise of single-parent families, the continued decline in unionization and the sharp increase in inequality, which has concentrated income gains at the top of the ladder. Your political views will probably determine the relative weights that you assign to those causes. Economic research hasn’t yet definitively answered the question.

Whatever the cause, though, the effects of the pay slump are going to be significant. Households have already begun to cut back their spending, and they will do so even more next year. Mr. Behravesh predicts that inflation-adjusted consumer spending in 2009 will be somewhere between flat and down 1 percent. If he’s right, it would be the first year that consumer spending didn’t grow since 1980, which just happens to be the last time that the country suffered through a deep recession.

The pay slump will also make it harder for people to pay off their loans. Last week, Bank of America reported that its losses on consumer credit had tripled over the last year.

In all, banks around the world have acknowledged $600 billion in losses as part of the financial crisis. The latest International Monetary Fund analysis suggests they still have another $800 billion in losses ahead of them — and a good chunk of them will occur in this country.

It’s always possible, of course, that some bit of good and unexpected economic news is just around the corner. The situation also seemed pretty dire in the mid-1990s, until the Internet boom came along and incomes then started rising at their fastest pace since the 1960s.

But you would have to be a pretty zealous optimist to forecast a repeat of that story. For two decades, consumer spending has been an enormous driver of economic growth, thanks in good measure to a long bull market, a housing bubble and a boom in consumer debt.

The bull market, the housing bubble and the debt boom have all ended — and now paychecks are shrinking, too.

At some point, the next big economic engine will indeed arrive. It always does. This time, however, it’s going to have some stiff head winds to overcome.

Paul Krugman

October 15, 2008, 11:51 amTrain headed downhill

It’s the real thing

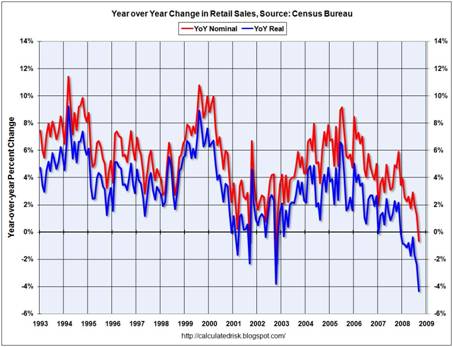

It’s the real thingThis chart comes from Calculated Risk, still my favorite housing-and-credit-bust site. It shows nominal and real retail sales, and shows that consumer spending is now plunging at serious-recession rates.

This reinforces a point I’ve been trying to make: even if the rescue now in train succeeds in unfreezing credit markets, the real economy has immense downward momentum. In addition to financial rescues, we need major stimulus programs.

October 15, 2008, 8:25 am

Nixonland

Meet the old boss

Meet the old bossThere are all sorts of connections between the Nixon administration and the Bush administration. But here’s one I didn’t know about: Hank Paulson was John Ehrlichman’s assistant in 1972 and 1973.

Maybe you have to have lived through Watergate to know what that means.

Two-Thirds Of The Benefits From McCain’s New Tax Cut Go To Millionaires

By at 11:25 amThink Progress.

As part of his new economic outline - The Pension and Family Security Plan - Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) has proposed cutting the tax rate on long term capital gains and dividends to 7.5 percent in 2009 and 2010. The current tax rate for these capital gains is 15 percent.

Today, the non-partisan Tax Policy Center (TPC) released an analysis showing who would benefit from this cut. Like the rest of McCain’s tax cuts, this one overwhelmingly aids the wealthy, with two-thirds of the benefit going to those making over $1 million:

In 2009, under a plan that lowers taxes on both gains and dividends, those making $1 million or more would get two-thirds of the benefit, and an average tax cut of more than $72,000. Those making less than $50,000 would get, on average, nothing.

As the TPC pointed out, “75% of the benefit of low taxes on capital gains and dividends already go to those making $600,000 or more. Half goes to those making $2.8 million or more.”

In fact, as the Wonk Room noted when McCain first toyed with including this provision in his economic plan, under the current 15 percent rate, 93.9 percent of the benefits go to the top 5 percent of taxpayers, and 84.8 percent to the top 1 percent. The other 80 percent of taxpayers see only 1.7 percent of the benefits of today’s rate.

The McCain campaign claims that the cut will “strengthen incentives to save, invest, and restore the liquidity of markets.” But given the current economic situation - one in which “people do not have an awful lot of capital gains” - this measure will do nothing to stimulate the economy.

Furthermore, The Street noted that McCain’s cut “might have unintended consequences,” like encouraging investors “to make one-time sales to capture lower capital gains and increased tax write-offs,” which “would facilitate capital flight.”

The Woman Greenspan, Rubin & Summers Silenced

posted by Katrina vanden Heuvel on 10/09/2008 @ 11:46pm

"Break the Glass" was the code-name high-level Treasury Department figures gave the $700 billion bailout; it was to be used only as a last- resort measure.

Now millions have been sprayed and damaged by broken glass.

But more than a decade ago, a woman you're likely never to have heard of, Brooksley Born, head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission-- a federal agency that regulates options and futures trading--was the oracle whose warnings about the dangerous boom in derivatives trading just might have averted the calamitous bust now engulfing the US and global markets. Instead she was met with scorn, condescension and outright anger by former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan, former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and his deputy Lawrence Summers. In fact, Greenspan, the man some affectionately called "The Oracle," spent his political capital cheerleading these disastrous financial instruments.

On Thursday, the New York Times ran a masterful and revealing front page article exposing the culpability of Greenspan, Rubin and Summers for the era of dangerous turbulence we live in.

What these "three marketeers" --as they were called in a 1999 Time magazine cover story--were adept at was peddling the timebombs at the heart of this complex crisis: exotic and opaque financial instruments known as derivatives--contracts intended to hedge against risk and whose values are derived from underlying assets. To cut to the quick, Greenspan, Rubin and Summers opposed regulating them. "Proposals to bring even minimalist regulation were basically rebuffed by Greenspan and various people in the Treasury," recalls Alan Blinder, a former Federal Reserve board member and economist at Princeton University, in the Times article.

In 1997, Brooksley Born warned in congressional testimony that unregulated trading in derivatives could "threaten our regulated markets or, indeed, our economy without any federal agency knowing about it." Born called for greater transparency--disclosure of trades and reserves as a buffer against losses.

Instead of heeding this oracle's warnings, Greenspan, Rubin & Summers rushed to silence her. As the Times story reveals, Born's wise warnings "incited fierce opposition" from Greenspan and Rubin who "concluded that merely discussing new rules threatened the derivatives market." Greenspan deployed condescension and told Born she didn't know what she doing and she'd cause a financial crisis. (A senior Commission director who worked with Born suggests that Greenspan and the guys didn't like her independence. " Brooksley was this woman who was not playing tennis with these guys and not having lunch with these guys. There was a little bit of the feeling that this woman was not of Wall Street.")

In early 1998, according to the Times story, one of the guys, Larry Summers, called Born to "chastise her for taking steps he said would lead to a financial crisis. But Born kept at it, unwilling to let arrogant men undermine her good judgment. But it got tougher out there. In June 1998, Greenspan, Rubin and the then head of the SEC, Arthur Levitt, Jr., called on Congress "to prevent Ms. Born from acting until more senior regulators developed their own recommendations." (Levitt now says he regrets that decision.) Months later, the huge hedge fund Long Term Capital Management nearly collapsed--confirming some of Born's warnings. (Bets on derivatives were a key reason.)

"Despite that event," the Times reports, " Congress (apparently as a result of Greenspan & Summer's urging, influence-peddling and pressure) "froze" Born's Commissions' regulatory authority. The next year, Born left as head of the Commission.Born did not talk to the Times for their article.

What emerges is a story of reckless, willful and arrogant action and behaviour designed to undermine a wise woman's good judgment. The three marketeers' disdain for modest regulation of new and risky financial instruments reveals a faith-based fundamentalist approach to the management of markets and risk. If there is any accountability left in our system, Greenspan, Rubin and Summers should not be telling anyone how to run anything. Instead, Barack Obama might do well to bring back Brooksley Born and promote to his team economists who haven't contributed to the ugly mess we're in.

(here's a flash from the past: before Reagan rewrote the tax code we, my husband and myself, wrote off the interest paid on credit card debit each year on our federal income tax. noodle that one for awhile.--java)

No comments:

Post a Comment