The Insurance Scandal: Just How Rotten?

The insurance industry is the latest financial sector to have its darkest secrets exposed to the light.

Economist Staff, The Economist

October 22, 2004

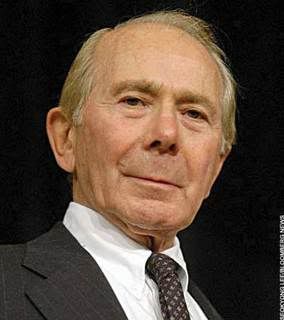

First came investment banking; then mutual funds; now the insurance industry is mired in scandal, the latest target of Eliot Spitzer, New York's formidable attorney general. On October 14th he filed civil charges against Marsh & McLennan, the world's biggest insurance broker, and announced settlements of criminal charges with two employees at AIG, the world's biggest insurer, and one at ACE, a big property-casualty insurer. The charges are part of an ongoing investigation into industry practices that suggest insurers and brokers have acted collectively (and secretly) to betray customers. An added twist is that the three main companies so far involved are led by members of the Greenberg family: Hank Greenberg is the legendary boss of AIG; his eldest son Jeffrey runs Marsh; and his younger son Evan is in charge at ACE. A business often thought to lack personality and drama is now suffering from an abundance of both.

Mr. Spitzer's civil complaint against Marsh, filed in New York state's Supreme Court, alleges much misbehavior, including fake bids, collusion, improper steering of business, payments by insurers to avoid solicitation of competing quotes, and outright threats against those resisting participation in the fraudulent schemes. Marsh acted, in short, less like a broker with a fiduciary obligation to its clients than as the linchpin of a racket. Proof for the existing charges, Mr. Spitzer contends, is "rock solid". Given the strength of the evidence and the seriousness of the infractions, the main legal conundrum he faced was whether he should file criminal rather than civil charges.

His leniency will be of only marginal solace for the industry. Mr. Spitzer says his investigation into insurance continues to expand, with the only certainty being that he will bring more charges against more people and more companies. So far only two segments of the vast insurance industry have been implicated — the mid-sized sector and so-called excess liability insurance (i.e., the umbrella policies companies buy to top off their core coverage), both prime territory for brokers.

But that looks certain to change. Mr. Spitzer is said to like cases that champion the average person, and he is going after general insurers too. Subpoenas from his office demanding information were reported to have been received this week by Aetna and Cigna (health insurance), MetLife (life insurance), and UnumProvident (disability). Shortly after the complaint against Marsh was disclosed, Aon, the second-largest brokerage firm, put out a statement that only a lawyer could find reassuring: the actions described in the complaint would have violated its own policies and "to the best of our knowledge" were not present at Aon. Mr. Spitzer's office quickly indicated that Aon is being examined with particular interest.

And Mr. Spitzer is not the industry's only legal threat. On October 19th and 20th Connecticut's attorney general sent out dozens of subpoenas to insurers operating in the state in the health, auto and employee-benefit sectors. In May he began investigating claims of widespread price-rigging and kick-backs. California began its own investigation of insurers and insurance brokers this spring. John Garamendi, the state's insurance commissioner, says he will soon bring civil charges against a number of companies, as well as introducing new rules to improve disclosure. Meanwhile, a barrage of private lawsuits has been filed in New York's federal district court, most of them against Marsh for misleading investors.

The embarrassment felt by the insurance industry is acute. But how did the problems arise? Few people outside the industry understand either its structure or how it has evolved in recent years. Essentially brokers are classic middlemen. They stand between companies that want to buy insurance and the insurers that sell it, taking a commission for services rendered. But the broker's job is no longer one of simply finding the lowest price. These days brokers help companies to prepare complex evaluations of their insurance needs, often in many different countries. That task requires knowledge of the insurance providers in each local market, but also a good understanding of local risks. Companies' proposals and risk assessments are used by insurers in making their bids; indeed, without the help of a broker many large companies would be unable to solicit meaningful offers from the big insurers. In effect, brokers serve as corporate advisers and form an important distribution channel for insurers. Since the brokers work for both sides, they have, increasingly, been paid commissions by both.

In their defense, brokers say these arrangements are disclosed to clients, and that, with adequate disclosure, the system can work. Yet disclosure is often vague, at best, and the potential conflicts are glaring. Indeed, Mr. Spitzer has revealed what amounts to gross abuse of the pricing system. Insurers have been offering incentives to brokers in the form of so-called "contingent commissions" — money paid only if the broker places a certain amount of business with a particular insurer.

Contingent Conflicts

Such commissions are generally calculated by the volume of business sent by a broker to an insurer — the more the better, regardless of whether it is in clients' interests. Less commonly, the commissions are based on the insurer's profits. But that can also harm customers, because a broker might choose not to push for a legitimate claim that will reduce the insurer's profits.

In the past some lawsuits have stemmed from these arrangements, notably a big case against Marsh and Aon in 2000. After a settlement, the testimony, evidence and disposition were subjected to a strict gag order, a common outcome in insurance cases. But legal momentum against contingent commissions has been building. The crucial breakthrough in Mr. Spitzer's investigation appears to have been the emergence during the past month of telling e-mails. According to the complaint, Marsh threatened to "kill" one insurance company if it did not provide sufficient commissions. ACE was told by Marsh that receiving more business would require the payment of "above market" commissions to Marsh (as opposed to lower rates to Marsh's clients).

Further, Marsh executives were rewarded for moving business to insurers paying high commissions and penalised when they did not. In one of the most egregious moves, Marsh reached a deal that linked the size of its contingent commission to AIG's ability to maintain prices on policy renewals. "Marsh is secretly raising the price of insurance for its clients and putting at least some of the increase into its own pocket," says the complaint.

As bad as this may seem, the most damning allegation is that Marsh took its desire to steer business to insurers one step further and actually rigged bids. The complaint describes a series of schemes whereby AIG would submit an uncompetitive "B Quote" against a rival's bid at a rate suggested by Marsh. Marsh would then show its customer what were apparently competing quotes, knowing that invariably the rival's cheaper quote would be accepted and that it would later pocket a contingent commission. In return, AIG would be allowed to win business in the future on similar terms.

Mr. Spitzer cites a specific example of ACE making a bid more costly at Marsh's direction to allow AIG to provide the low offer on renewal of a policy with Fortune Brands, an American conglomerate. The Hartford, another American insurance giant, went along with similar schemes, according to the complaint, "because Marsh was its biggest broker, and it felt that Marsh would limit its business opportunities if it refused." Munich-American RiskPartners, the American subsidiary of Munich Re, was asked so frequently by Marsh for a "live body" to attend client presentations for the sake of appearing to provide competition that a manager sent a message to Marsh: "While you may need 'a live body', we need a 'live opportunity'." In an internal memo, a Munich-American manager characterised quoting artificially high quotes as "basically dishonest" and "awfully close to collusion or price fixing."

After the charges were announced, shares of ACE and AIG fell by more than 10 percent and Marsh's by more than one-third. Tellingly, the share price of every other insurance company and broker fell as well. Marsh's market value has now halved, while AIG's is lower by $24 billion.

However, it is unlikely that any company will be driven out of business as a result of the scandal. Even Marsh might not be hit as badly as it may deserve. Typically, the risk departments of companies begin discussions about renewing their annual policies on September 1st, in order to allow for an orderly transfer at the end of the year. It may already be too late for them to go through the lengthy assessment and solicitation process with another broker. There is also a scarcity of choice. Consolidation has boiled down the number of truly global brokers to just three — Marsh, Aon and Willis. There could be a big shift if one of these were to be given a clean bill of health. In the meantime, Marsh, unlike an insurance company, faces no counterparty risk and thus should avoid the kind of fatal spiral that can hit a leveraged financial firm during a panic.

Marsh's Quadruple Whammy

Whether Marsh survives in its current form, however, is another question. Mr. Spitzer says Marsh's bosses have not been "sufficiently forthcoming, open or honest to persuade me that they are the appropriate leadership if this is to be a reformed company." Marsh's Putnam asset-management division was caught up in the mutual-fund scandal and its Mercer consulting unit is currently being investigated for its pension recommendations and also played a controversial role in the huge compensation package that was awarded to Richard Grasso, former boss of the New York Stock Exchange who is also being prosecuted by Mr. Spitzer.

Presumably Marsh's board is gearing up to make big changes — Mr. Spitzer says he will not settle charges with the current top team. Shrewdly, on October 15th Marsh appointed Michael Cherkasky as the group's new boss. He recently led Kroll, Marsh's corporate-investigation subsidiary, previously part-owned by AIG. In the distant past, Mr. Cherkasky did a stint supervising a young Mr. Spitzer in the Manhattan district attorney's office.

But even if only some of today's top management survives, Marsh is badly bruised. It has suspended taking any contingent commissions, and revealed that these amounted to $845 million last year, 7 percent of revenues but, more tellingly, one-third of its pre-tax profits. It might have to give all of that back. And anything short of a victory in court will trigger a large fine.

AIG has also been battered. The scandal comes on top of investigations by both the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Justice Department for work it did structuring off-balance-sheet entities for PNC Bank and possibly other companies as well. In a conference call with analysts, Mr. Greenberg said the loss of contingent commissions would have no business consequences, but that seems naive coming from one so experienced. Losing access to a price-rigging cartel can surely only increase competition.

Inevitably, this will affect other insurers, putting structural pressure on prices just as cyclical factors suggest rates are softening. And still unclear is what sort of broad resolution Mr. Spitzer might seek. In prior investigations, his style has been to use the threat of litigation to force through agreements that include lots of money, carefully scripted non-confessions of guilt, and widely trumpeted vows of reform. The results have often been disappointing. It is probably no coincidence that agreements with investment banks and mutual funds have resulted in money moving to less-regulated areas, namely private equity and hedge funds. Insurance more than perhaps any other industry is global, so an inappropriate move by Mr. Spitzer would surely send business overseas.

Europe Looks On

But might the rot have already spread overseas? For the moment European insurers are on the periphery of the American scandal. Only Germany's Munich Re, the world's biggest reinsurer, and Zurich Financial Services, a Swiss insurer, were mentioned in Mr. Spitzer's complaint and neither is accused of any wrongdoing.

Further, Europe does not have an equivalent of Mr. Spitzer, and regulators in Europe are not currently intending to investigate relations between insurers and brokers. So only European insurers with a presence in America risk being directly involved in the scandal for the moment. Swiss Re writes 40 percent of its property and casualty business in America, although only 20 percent of these contracts are done via brokers. A similar portion of Zurich Financial Services' non-life policies are written in America, mostly directed through brokers.

All the same, European financial markets reacted nervously, and shares in Munich Re, Allianz and AXA all fell. The unknown factor is whether Europeans have also been corrupt. After all, the temptation facing brokers is the same everywhere. Like their American counterparts, European insurers pay brokers contingent commissions. Brokers also demand that insurers provide reinsurance work in exchange for referrals. Criticisms of these practices used to fall on deaf ears. "We consider contingency fees an aberration and we have been asking brokers since 1998 to abolish them," says Thierry van Santen, head of the Federation of European Risk Management Associations in Brussels.

German insurers claim they are not aware of any unsavory practices at home. For one thing, the use of intermediaries is less common. In many cases Allianz, Europe's biggest insurer, and Munich Re deal directly with clients. Moreover, Lufthansa, Siemens and other big firms have in-house brokers, which are not conflicted. Even so, American brokers have made inroads in the German market in recent years. Today the country's biggest broker is Aon Jauch & Hübener, a subsidiary of Aon. It is followed by Marsh, which expanded in 1999 when it took over Gradmann & Holler, a broker in Stuttgart.

German brokers are not regulated by BaFin, the country's financial regulator, but rely on a consensus-based system of self-regulation. The VDVM, an association of German insurance brokers, recently developed an ethics code for its more than 570 members. It now wants to speed up the implementation of these guidelines.

In France insurers and brokers profess to be shocked by Mr. Spitzer's discoveries. Leading French brokers such as Fimat claim they are more transparent about their fees than rivals in other countries. They are, at least in theory, regulated by an agency under the wings of the economics ministry. According to French insurance legislation, the agency "can" oversee brokers. In reality they look after themselves, much like their German colleagues. In 2001 they agreed their own code of conduct when one of their main trade unions jointly developed new guidelines with France's association of risk managers.

But brokers in France and Germany will soon lose some of their independence. The European Union's Insurance Mediation Directive aims to bring all parties involved in the sale of insurance under the jurisdiction of one national regulator. The directive comes into effect next January, although it is being resisted fiercely by insurance lobbyists, so it will take even longer than usual for member states to implement the law. One obvious hurdle is that France and Italy, among others, do not have a single financial regulator.

A British Disease?

Mr. Spitzer's charges have raised most alarm in Britain. As in America, the business there is dominated by a handful of brokers. Aon has 25 percent of the British market, and Marsh is also a leading broker. Britain has several good-sized insurance brokers of its own. Willis is headquartered in London; others include Jardine Lloyd Thompson (JLT) and Benfield, a reinsurance broker. Benfield does about 40 percent of its business in America and has been contacted by Mr. Spitzer, but says it does not accept contingent commissions. JLT says such commissions account for just 2 percent of revenue. Though share prices in both companies dropped in the wake of Mr. Spitzer's announcement, researchers at UBS, an investment bank, say that Marsh's stumble could mean more business for them. Justin Bates of Numis, an institutional broker, says Mr. Spitzer's charges may stop both firms from being snapped up by the big three as insurance pricing softens.

Many people expect British regulators to launch their own investigation. But that will not happen immediately. The General Insurance Standards Council, the current regulator, says that it has no interest in a "fishing expedition" in the absence of a complaint. It is more likely, then, that the Financial Services Authority (FSA), which takes over the regulation of insurance brokers next January, will follow up on Mr. Spitzer's complaints.

Though the FSA says that it is "monitoring the situation", it has taken its cue from Mr. Spitzer before on matters such as market-timing (a sin of mutual-fund managers) and investment banks' allocating of shares in hot initial public offerings to preferred clients. On both those counts, Britain has avoided the worst abuses (though there have been plenty of other financial-services scandals). The industry is cringing at the notion of the FSA demanding yet more information on top of the existing deluge of paperwork. But that might prove a small price to pay if the result is that it avoids the punishments facing American firms. The insurance industry's moment in the spotlight is far from over.

The nation's number one corporate crime buster, New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, launched his campaign for higher office in December, announcing that he was running for Governor of New York, the next step in his quest for the presidency.

Spitzer is out to prove that projecting a tough cop image against corporate crime pays dividends — as long as you pull your punches when it comes to settlement time.

When Spitzer announced in November that he was opening a new front against the insurance industry, there was the usual quaking in the boots by the Wall Street Journal and the other lead megaphones for big business, charging Spitzer with using his law enforcement powers to force changes in business practices.

And have no doubt — the corporate lobbies would prefer a do-nothing law enforcement agency to an activist one, even a mildly activist one.

That's why they rail against Spitzer, and even against SEC chair William Donaldson, a former chief executive himself and friend of the Bush family.

Big business now reportedly wants even Donaldson removed from office for his mild activism.

But when push comes to shove, there is no shoving allowed by prosecutors. If you do shove, or push too hard, you will not be allowed to proceed up the political ladder. Period. End of story.

Spitzer sent clear signals when he started his crusade against Merrill Lynch.

Remember the Merrill Lynch analysts who told their customers — trust me, buy this stock, this stock is highly rated?

And then they would turn around and e-mail their buddies — hey, this stock is lousy, why are we recommending this stock to our customers?

Spitzer got his hands on the e-mails, charged Merrill with violating the law and forced them to pay $100 million.

But he got Merrill to pay up only by agreeing not to criminally prosecute the company.

Spitzer later admitted that had he forced Merrill to admit wrongdoing, the firm would have gone kaput.

Just like Arthur Andersen.

In October, 2004 Spitzer moved against a major insurance broker, Marsh & McLennan, alleging that the company steered unsuspecting clients to insurers with whom it had lucrative payoff agreements, and that the firm solicited rigged bids for insurance contracts.

By threatening criminal action, Spitzer forced the company's CEO to resign — and replaced him with a former work colleague.

Major insurance companies — ACE, American International Group, The Hartford and Munich American Risk Partners — were named in the complaint as participants in steering and bid rigging. Other insurance companies are still under investigation.

Here's a prediction — Marsh & McLennan will not be convicted of any wrongdoing. Why? Because Spitzer fears, as he feared in the Merrill case, that forcing a company to admit to guilty would push it to the brink — à la Andersen.

Andersen's conviction sent a powerful message to big business — engage in criminal wrongdoing, and you will be criminally prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

Too powerful, as it turns out.

So, with the Merrill case, Spitzer has started a trend.

Yes, prosecute corporate crime, but don't force companies to admit guilt.

Thus, when the world's largest insurer, American International Group Inc. (AIG), was charged by federal prosecutors with crimes in November, it quickly cut a deal with the Justice Department that ended a criminal probe into its finances with a deferred prosecution agreement.

In a deferred prosecution, the corporation accepts responsibility, agrees not to contest the charges, agrees to cooperate, usually pays a fine and implements changes in corporate structure and governance to prevent future wrongdoing.

If the company abides by the agreement for a period of time, then the prosecutors will drop the criminal charges.

In a non-prosecution agreement — like the one secured by Merrill Lynch's in 2003 with New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer — prosecutors agree not to bring criminal charges in exchange for corporate fines, cooperation and a change in corporate structure and governance.

“This comprehensive settlement brings finality to the claims raised by the SEC and the Department of Justice,” said AIG Chair M. R. Greenberg. “The role of the independent consultant complements our own transaction review processes. We welcome this enhancement to our overall risk management and control mechanisms.”

“We have always sought to adhere to the highest ethical standards and ensure that we are in compliance with the applicable laws and regulations that govern our businesses around the world. As part of this effort, we regularly review our compliance policies and procedures and take additional action whenever appropriate to enhance them.”

Under the deal with AIG, an AIG subsidiary was charged with a crime for the next 12 months, but then the charge will be dismissed with prejudice — if AIG abides by the deferred prosecution agreement.

As part of the agreement, AIG and two subsidiaries will pay an $80 million penalty, and $46 million into a disgorgement fund maintained by the SEC.

Federal officials in October filed a criminal complaint charging AIG-FP PAGIC Equity Holding Corp., a subsidiary of AIG, with violating the federal securities laws, by aiding and abetting PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. (PNC) in connection with a fraudulent transaction to transfer $750 million in mostly troubled loans and venture capital investments from subsidiaries off of its books.

These transactions were previously the subject of a deferred criminal disposition involving PNC.

Earlier this year, the Department dismissed the criminal complaint against a PNC subsidiary, after the company fulfilled its deferred prosecution agreement obligations.

Merrill, AIG and PNC are three of 10 major corporations that have settled serious criminal charges with deferred prosecution, no prosecution or de facto no prosecution agreements over the last two years. The other seven are Computer Associates, Invision, AmSouth Bancorp, Health South, Banco Popular de Puerto Rico, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce and MCI. Bank of New York is currently seeking a similar deal with prosecutors in Brooklyn.

Companies are getting off the criminal hook with these agreements, which were originally intended for minor street crimes.

Now they are being used in very serious corporate crime cases.

If a crime has been committed — and there is little doubt that crimes have been committed by the corporations in these cases — then the companies should plead guilty and pay the penalty.

If prosecutors want to impose change on the corporation, they can do this after securing a conviction through probationary orders.

Right now, corporate lawyers are teaming up with prosecutors to go after individual executives while the company's record is wiped clean.

No comments:

Post a Comment