Treasury and the Fed Looking at Options

WASHINGTON — For the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department, the crisis continues.

Without the broad bailout plan they invented and lobbied hard for, the two agencies are once again forced to careen from one desperate path to another, and to dig deep into their toolkits to rescue the global financial system. Even before the House stunned the world on Monday by rejecting the Bush administration’s bailout bill, the Fed was already resorting to the oldest action in its book: printing money.

With money markets around the world seizing in fear, the Fed on Monday announced that it would provide an extra $150 billion through an emergency lending program for banks, and an additional $330 billion through so-called swap lines with foreign central banks to help money markets from Europe to Asia.

It was an extraordinary display of financial power, and it reflected acute new anxiety at the Fed and central banks around the world that the crisis of confidence in American financial markets had metastasized to money markets everywhere.

That was on top of the $230 billion the Fed borrowed last week so it could finance its previous efforts to prop up the American International Group and other institutions. But these are only the latest in a long series of jaw-dropping departures from normal policy that the Fed has undertaken this year as it seeks to inject vast amounts of capital into the financial system. And they are unlikely to be the last.

Even if Congress refuses to pass the bailout measure, there is more money where that came from. The Treasury Department has already created a series of “supplemental” Treasury securities to finance the Fed’s activities, and there is no limit to how many more it can issue and sell.

Treasury and Fed officials made it clear after the House vote on Monday that they still had a wide range of tools at their disposal. But most of the remaining options are ad hoc, rather than systemwide. The Fed, for example, can lend money to any company it deems too dangerous to fail by invoking the same Depression-era law it has already used to deal with failing firms like Bear Stearns and A.I.G.

The Treasury Department, meanwhile, has already vowed to buy up billions of dollars in mortgage-backed securities under the authority it received in the housing bill that Congress passed in the summer.

The bad news is that those attempts have done little or nothing to bolster confidence in the financial markets. Yields on three-month Treasury bills shrank to just 0.29 percent on Monday, a sign that investors were fleeing from any kind of risk, even if it meant earning a return far lower than the inflation rate.

Interbank lending rates climbed to new highs on Monday, as banks became even more fearful about lending to one another than they were last week.

“The liquidity measures are a stopgap,” said Laurence H. Meyer, vice chairman of Macroeconomic Advisers, a forecasting firm. “You’re funding the banks’ balance sheets, but nobody wants to lend money to them because they’re all afraid of insolvency.”

Administration officials were shocked at the House’s refusal to approve their bailout plan but are still hoping to rescue the plan later this week, by offering some modifications that will win over rebellious House Republicans without losing crucial Democratic votes.

“We need to put something back together that works,” said Treasury Secretary Henry M. Paulson Jr. Though he promised to “use all the tools available to protect our financial system,” he warned that “our toolkit is substantial but insufficient.”

In the absence of broader authority, Treasury officials are reviewing the options for creatively using the same kinds of case-by-case actions they have taken over the last six months — taking over Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, bailing out A.I.G., and arranging shotgun marriages between failing institutions and healthy ones.

Robert A. Dye, chief economist at PNC Financial in Pittsburgh, said those efforts amounted to patchwork solutions and had thus far failed to bolster confidence in credit markets.

“The problem is that these are just a series of ad hoc solutions on a business-by-business basis, and they aren’t addressing the systemic problems in any basic way,” Mr. Dye said.

But other analysts said that credit markets around the world were almost entirely dysfunctional on Monday morning, when political leaders and investors alike assumed that Congress had reached a firm deal and would easily approve the bailout.

“It’s our view that this package, in a fundamental sense, will not solve the problem,” said Simon Johnson, a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. Mr. Johnson said that he had been hoping that the bailout plan would simply stabilize the markets through the presidential elections in November, but that he was now pessimistic about even that.

Michael Darda, chief economist at MKM Partners, an investment firm in Greenwich, Conn., said the Treasury’s bailout plan might have even unnerved many investors.

“I don’t see how it can help banks unless it’s clear that the government is going to buy these assets for substantially more than they are worth right now,” Mr. Darda said. “It’s such a big step in terms of government influencing the private sector, and it’s hard for investors to take a leap like that overnight, especially when they don’t know what’s going on.”

The Federal Reserve has stretched its resources to the limit. Before the crisis began in August 2007, the Fed had about $800 billion in reserve, nearly all in Treasury securities.

But because of all the new lending programs for banks and Wall Street firms, analysts estimate that the Fed’s balance sheet now has less than $300 billion in unfettered reserves.

The central bank can expand its reserves at will, because it controls the money supply and can create more to buy things like Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities.

“We have a lot of money to play with,” said Kenneth Rogoff, an international economist at Harvard. “As long as foreigners have a lot of confidence in our ability to solve our problems, we can borrow the $1 trillion to $2 trillion we need to solve it.”

But Mr. Rogoff cautioned that the real limitation for American policy makers is whether they can maintain the government’s long-term credibility. “The real constraint is not a bookkeeping one,” he said. “It is a sense of faith on the part of foreigners that the U.S. government will repay its debt. Our most precious asset is that credibility.”

As risk grows, resources strained at Fed, FDIC

By Peter G. Gosselin and James PuzzangheraLos Angeles Times Staff Writers

September 30, 2008

WASHINGTON — If the House vote against the $700-billion financial rescue proposal stands, Americans may be in for a test of free-market economics the likes of which the country hasn't seen since the early 1930s.

With the Treasury Department hobbled by the rejection of its plan, the Federal Reserve and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. are the chief government institutions standing between the nation and the brutally Darwinian process that could unfold if the panicky financial markets are left to sort their problems out alone.

It's an open question whether those two institutions acting alone have the resources and power to avert such a debacle -- the cascading failure of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of financial institutions and paralysis spreading across the whole economy.

"We're entering a new phase of the crisis," said Chris Rupkey, chief financial economist with the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi in New York. "If you don't stop the domino effect, you're going to see one institution after another after another going down," he predicted.

That's something the United States last experienced in the early 1930s, when Herbert Hoover was in the White House. Some conservatives believe that's still the best long-term solution to the problem, though none has gone so far as Hoover's Treasury secretary, Andrew Mellon, who said: "Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate. . . . It will purge the rottenness out of the system."

But House members and their supporters who insisted Monday that the government had no business staging a massive intervention in the financial marketplace were essentially making a modern-day argument for the laissez-faire economic policies of the Mellon era.

For now, the Fed and FDIC are doing what they can.

Early Monday, the Fed pumped an extra $630 billion into banks around the world. Its goal: to keep money flowing through the financial plumbing that's hidden from view but is crucial to the global economy's operation.

Meanwhile, the FDIC, for the second time in a week, orchestrated the safe demise of a major bank, this time helping engineer the sale of Wachovia Corp., the nation's fourth-largest bank by assets, to Citigroup Inc.

The deal puts Washington on the hook if losses in Wachovia's $312-billion loan portfolio top $42 billion.

But the two government agencies are severely limited in what they can do to keep the crisis from affecting ordinary Americans.

For the Fed, the problem is that with business confidence so shaken, the banks on the receiving end of its latest flood of cash are parking the money in their vaults rather than lending it out to keep the economy functioning. Bankers worry that they might need the money if conditions keep getting worse.

"They won't even lend it to each other," said Brookings Institution economist Robert E. Litan, "and if they're not going to lend it to each other, they certainly aren't going to lend it to you and me."

The lending drought means that people are having a harder time borrowing to buy houses, cars and appliances, and business are having a harder time generating sales.

Little cash is available for growth and job creation. But there's a more immediate danger: To an extent little appreciated by most Americans, businesses today no longer pay for their day-to-day operations with their own money but do so with borrowed funds.

Making next week's payroll or buying the supplies workers need to do their jobs tomorrow depend on loans. Without those loans, companies and the economy as a whole begin to grind to a halt.

The slowdown is feeding other problems that plague the nation: plunging home prices, the imploding value of mortgage securities and collapsing confidence. Among other things, that's all but certain to push more financial firms over the edge.

When that happens, the Fed and the FDIC have only one course of action: to pick and choose among collapsing firms, deciding which ones get a soft landing and which ones crash.

And the ad-hoc rescue efforts create damaging ripples of their own.

"It's very difficult for the market to know how to react when each government intervention is different," complained Jaret Seiberg, a financial services analyst with Stanford Group. "There's no rhyme or reason, and that leads to more market instability."

There's another problem with leaving the solution to the financial crisis to the Fed and the FDIC: Though they have yet to reach it, each probably has a limit to its capacity to make rescues.

For the Fed, the constraint is not the central bank's ability to pump out cash, which is essentially limitless. Instead, it's the quantity of the risky securities of troubled financial firms it can take on its books -- as collateral for the loans it makes to the firms -- without weakening its own financial condition.

Since the beginning of the year, Fed records show that the proportion of outside securities on the central bank's books has climbed to about 60%, while the fraction of risk-free U.S. Treasury securities among its assets has dropped from 90% to 40%.

Fed officials assert that the change doesn't limit the central bank's ability to act, but outside analysts such as Brookings economist Litan are not so sure. "The Fed is looking more and more like any other private financial institution," he said.

In the case of the FDIC, the limit is the size of the fund that insures bank deposits. The fund had $45.2 billion as of June 30, raised from premiums paid by banks. The FDIC plans to increase those premiums, although it's unclear that the rise will be substantial, given the current crisis. In addition, it can borrow up to $30 billion from the Treasury.

If Washington's rescue resources were to run out, the nation's investors, traders and lenders could discover that it was up to them alone to right the financial system.

That's a situation that has not occurred in more than three-quarters of a century, during the Great Depression.

"This is smacking more and more of the late 1920s and early 1930s," said New York University economic historian Richard Sylla.

In fact, in a less disastrous manner than during the Depression, something like Mellon's prescription of across-the-board liquidation is now underway.

And without a big, new program like the one rejected by the House on Monday, there is only so much the existing institutions can do.

The FDIC's scope is limited. And, Rupkey said, "the Fed's balance sheet is about to explode."

peter.gosselin@latimes.com

LONDON: The cost of borrowing in dollars surged the most on record Tuesday after the U.S. Congress rejected a $700 billion bank rescue plan, heightening concern more institutions will fail.

The London interbank offered rate, or Libor, that banks charge each other for such loans climbed 431 basis points to an all-time high of 6.88 percent Tuesday, the British Bankers' Association said. The euro interbank offered rate, or Euribor, for one-month loans climbed to record 5.05 percent, the European Banking Federation said. The Libor-OIS spread, a gauge of the scarcity of cash, advanced to a record. Rates in Asia also rose.

"The money markets have completely broken down, with no trading taking place at all," said Christoph Rieger, a fixed- income strategist at Dresdner Kleinwort in Frankfurt. "There is no market any more. Central banks are the only providers of cash to the market, no-one else is lending."

Credit markets have seized up, tipping banks toward insolvency and forcing U.S. and European governments to rescue five banks in the past two days, including Dexia, the world's biggest lender to local governments, and Wachovia. Money-market rates climbed even after the Federal Reserve Monday more than doubled the size of its dollar-swap line with foreign central banks to $620 billion. Banks borrowed dollars from the ECB at almost six times the Fed's benchmark interest rate Tuesday.

The two-month Libor rose to 5.13 percent Tuesday, also a record. Libor, set by 16 banks including Citigroup and UBS in a daily survey by the BBA, is used to calculate rates on $360 trillion of financial products worldwide, from home loans to credit derivatives.

Funding constraints are being exacerbated as companies try to settle trades and buttress balance sheets over the quarter-end, balking at lending for more than a day.

"Counterparty fear in the banking sector is at a new extreme," said Greg Gibbs, director of currency strategy at ABN Amro Holding Bank in Sydney. "Credit conditions are as tight as a drum. Unless this settles down, central banks would need to cut rates globally to bring funding costs down."

The ECB said it lent banks $30 billion for one day at a marginal rate of 11 percent. The Fed's key rate is 2 percent. The ECB said it received bids for $77.3 billion. The Bank of Japan injected more than ¥19 trillion, or $182 billion, into the country's system over the past two weeks, the most in at least six years. The Reserve Bank of Australia pumped in A$1.95 billion, or $1.6 billion, Tuesday.

Click here to view the video explaining LIBOR: http://www.learningmarkets.com/index...sis&Itemid=380

Why are Economists Worrying About a Rising LIBOR?

In the midst of the largest financial crisis since The Great Depression, you are probably hearing a lot about LIBOR rising—which is a sign that the global credit markets are seizing up because banks are afraid to loan to each other because they don't know if the other banks they are loaning to are going to exist next week, let along be able to pay back those loans. But what on earth is LIBOR? (Video Below) LIBOR - London Interbank Offered Rate

London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR)

The financial markets are full of acronyms, and one of my favorites is LIBOR. The acronym LIBOR stands for London InterBank Offered Rate. This is the average interest rate that banks charge when they make short-term unsecured loans to other banks.

Unlike the Federal Funds Rate or the Discount Rate, which are both set by the U.S. Federal Reserve, nobody "sets" the LIBOR rate. Instead, the British Bankers' Association (BBA) surveys 16 different major banks and asks them what rate they are charging other banks to borrow money. Once they have compiled the results, they take an approach similar to the judges who score Olympic diving take—they throw out the four high scores (or rates) and throw out the four low scores and then find the average of the remaining eight scores. Here's how it works:

Imagine the BBA goes out, surveys its 16 banks and ends up with the following interest rates being charged by each bank:

- Bank #1 — 3.87%

- Bank #2 — 3.85%

- Bank #3 — 3.81%

- Bank #4 — 3.76%

- Bank #5 — 3.75%

- Bank #6 — 3.74%

- Bank #7 — 3.71%

- Bank #8 — 3.69%

- Bank #9 — 3.67%

- Bank #10 — 3.66%

- Bank #11 — 3.63%

- Bank #12 — 3.62%

- Bank #13 — 3.60%

- Bank #14 — 3.57%

- Bank #15 — 3.53%

- Bank #16 — 3.48%

In this case, the BBA would throw out the top four rates (Banks 1–4) and the bottom four rates (Banks 13–16) and then average the rates from the remaining banks (Banks 5–12) to come up with a LIBOR rate of 3.68 percent.

The BBA conducts these surveys and then calculates the LIBOR rate once a day at about 11 am London time.

What Does LIBOR Tell Us?

When LIBOR is rising, it tells us one of two things: 1) it tells us that interest rates in general are rising and thus LIBOR is also rising, and/or 2) it tells us that lending banks believe the banks they are lending to have a higher risk of defaulting on the loan so the lending bank has to charge a higher interest rate to offset this risk.

When LIBOR is falling, it tells us one of two things: 1) it tells us that interest rates in general are falling and thus LIBOR is also falling, and/or 2) it tells us that lending banks believe the banks they are lending to have a lower risk of defaulting on the loan so the lending bank does not have to charge a higher interest rate to offset this risk.

You can also compare LIBOR to other indicators to conduct spread analyses, like the LIBOR OIS Spread (more on this later).

What's Responsible for the TED Spread's Recent Behavior?

One measure that is being used to summarize the strain in financial markets is the TED spread. This is calculated as the gap between 3-month LIBOR (an average of interest rates offered in the London interbank market for 3-month dollar-denominated loans) and the 3-month Treasury bill rate. The size of this gap presumably reflects some sort of risk or liquidity premium. I was interested to break the TED spread down into identifiable components to try to get a better understanding of what may be responsible for its recent behavior.

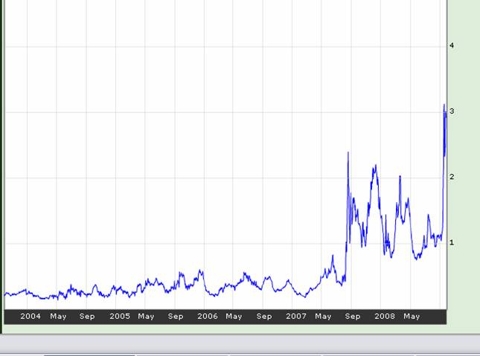

The TED spread over the last 5 years is plotted below; for a longer time series see Bespoke Investment Group. Historically the spread typically stayed under 50 basis points. However, it's usually been above 100 basis points since the credit events of August 2007, and reached 300 several times during the last two weeks.

|

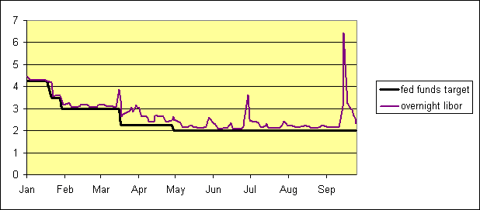

The overnight interest rate on loans between banks in the U.S. money market is the fed funds rate, whose average value is set as the primary target of U.S. monetary policy. There is also an overnight LIBOR rate, whose borrowers and lenders include some of the same banks that participate in the U.S. federal funds market, albeit a little earlier in the day. As a first step to understanding the LIBOR-TBILL spread, I was curious to look at the difference between the overnight LIBOR rate and the fed funds target. This had a rather impressive spike September 16-17.

|

Why would a bank want to borrow overnight dollars for 5-6% in London when it could be assured of obtaining those same funds for 2% later that day in New York? For one thing, the situation was sufficiently chaotic two weeks ago that many banks in fact were unable to borrow in New York at 2%. The effective fed funds rate (a volume-weighted average of all the known U.S. trades on a given day) was 2.64% on Sept 15 and 2.80% on Sept 17, despite the Fed's intention to keep these numbers around 2.0. Somebody who was worried about how these days were going to unfold may have quite rationally bid quite a bit to secure the funds early. Or perhaps the U.S. banks dropped out of the London market altogether. In any case, a one- or two-day spike in this overnight rate is not that big a deal, since even a few hundred basis points (at an annual rate) is not that much money on a one-day loan. Following that impressive but brief spike, overnight LIBOR is now back to 2.31%, a modest 31 basis points over the Fed's target.

One can break the TED spread down into separate components using the following accounting identity. Let LIBOR3 denote the 3-month LIBOR rate, LIBOR0 the overnight rate, TARGET the fed funds target, and TBILL the 3-month Treasury bill rate. The TED spread is defined as

TED = (LIBOR3 - TBILL)

which can be rewritten as

(LIBOR3 - TBILL) = (LIBOR3 - LIBOR0) + (LIBOR0 - TARGET) + (TARGET - TBILL)

As just discussed, the middle term above, LIBOR0 - TARGET, is at the time of this writing back to usual values, so the bloated value for the TED spread must be coming from a combination of the first and last terms. Indeed on Friday, the spread between the 3-month and overnight LIBOR rate stood at 145 basis points:

(LIBOR3 - LIBOR0) = 1.45

Why is the 3-month rate so much higher than the overnight rate? It certainly can't be an expectation that the Fed's target for the overnight fed funds rate is about to increase. If the Fed makes a move over the next 3 months (and it very well could), it would be for a decrease, not an increase, in the target. The LIBOR term spread must therefore be interpreted as some sort of a liquidity or risk premium. If I lend you funds overnight, I should have a pretty good idea of whether there's some news coming within the next 24 hours that would prevent you from repaying. I may correctly judge that risk to be small. But over the next 3 months, who knows what might happen? If I were a risk-neutral lender, and I thought there was a 0.36% chance that a currently sound bank may go completely bankrupt over the next 90 days, I'd want a 145-basis point (annual rate) premium on the 3-month loan as compensation. If I were risk averse, I would require that 145-basis-point compensation even with a much lower probability of default.

Or, it may be that I'm afraid I myself might be exposed to some severe credit event over the next 3 months, and would be better off keeping any extra cash in Treasuries rather than lending them 3 months unsecured. I would describe this consideration as a "liquidity premium" as opposed to a "risk premium".

If leading financial institutions are making these sorts of assessments of the probabilities of risk or liquidity needs, it bespeaks a very unsettled financial market that is apt to function poorly at channeling funds to any of the other inherently risky economic investments whose funding is vital for a functioning economy.

But this risk/liquidity premium only accounts for half of the TED spread. The remainder is due to the gap between the fed funds target (currently 2.0%) and the yield on 3-month Treasuries (now under 1%). This is the other part of the "flight to quality" just discussed. But on the other hand, the (TARGET - TBILL) gap is also a deliberate choice of policy. The Fed could simply lower its target for the fed funds rate, and chase the T-bill rate down to zero, if it wanted.

What's the downside to that? Here's the next shoe that could drop: the financial dislocations could lead to a perception by global investors that the U.S. is no longer a safe place to be putting their capital, which could add a currency crisis component to the present financial turmoil. Greg Mankiw notes this report:

China's government moved to calm financial markets Thursday and denied a report that it had ordered mainland banks to curb lending to U.S. banks, a day after rumors of financial stability led to a run on a Hong Kong institution.

Calm again for the time being, I guess. But if a cut in the fed funds rate leads to rapid dollar depreciation and commodity inflation, it could be pulling the trigger on something even scarier than what we've seen so far.

Not an attractive set of options on the menu for the FOMC.

No comments:

Post a Comment